Portland marijuana company Cura Cannabis sells for $1 billion

Portland-based Cura Cannabis sold Wednesday for more than $1 billion in an all-stock transaction, the largest deal ever among American companies operating in the legalized marijuana business.

Cura sells its cannabis oils on the wholesale and retail market under the Select brand and operates in California, Arizona and Nevada.

The buyer is a Massachusetts company called Curaleaf Holdings, whose shares trades on the Canadian market.

The companies valued the transaction at $949 million based on Curaleaf’s closing stock price Tuesday. But the Massachusetts company’s shares jumped 12 percent Wednesday on word of the transaction, inflating the deal’s value to nearly $1.1 billion, on paper at least.

The deal marries Curaleaf’s focus on the eastern United States with Cura’s markets in the West. The size of the transaction underscores the enormous potential investors see in the market for legalized marijuana and the rapidly evolving commercial landscape within the cannabis sector.

“The transformational acquisition of Cura and the Select brand is another step in our journey to create the most accessible cannabis brands in the U.S.,” Joseph Lusardi, Curaleaf’s chief executive, said in a written statement.

Cura says it has 500 employees and had revenue of $117 million last year, triple its revenue from 2017. It’s actually larger than Curaleaf, which reported $87.8 million in revenue last year.

The combined company will operate in 15 states where marijuana is legal.

The Portland company’s chief executive, Cameron Forni, will become Curaleaf’s president. He said “The leading companies in the industry on the West Coast and the East Coast are now joining forces to progress the legalization and mainstream acceptance of cannabis across the country.”

Cura Cannabis, Portland’s billion-dollar marijuana company, has a tortured past

It’s an eye-popping figure,

the billion dollars a Massachusetts company called Curaleaf Holdings agreed to pay Wednesday for a Portland marijuana startup, Cura Cannabis.

The scale of the deal underscores the enormous potential investors see in the market for legalized marijuana. When it comes to Cura, though, that’s just a piece of the story.

Cura is a wild tale with many twists beginning at Iris Capital Management, a notorious real estate scandal that earned the man who founded both Cura and Iris a three-year sentence in federal prison.

It’s the story of bad investments, bad choices, an explosive rape allegation, and years of lawsuits and recriminations. It’s the story of a recreational marijuana industry that remains shadowy five years after Oregon voted to legalize it.

And it’s the story of nearly 50 Oregon retirees – university professors, marketing professionals and health care executives among them – who lost $1 million in retirement savings in the real estate scam that birthed Cura, the company that sold for $1 billion on Wednesday.

“It’s astonishing,” said one of the scam’s victims, a retired university professor who said she lost more than $100,000 in the real estate scam. She asked not to be identified as the victim of a real estate scam.

Cura settled claims against it from the real estate scandal in 2016 for a little more than $500,000 without objection from the scam’s victims. That means the retirees will get none of the $1 billion from Wednesday’s deal, a development that leaves the woman, age 75, incredulous.

“We got $500,000 and they sold for a billion dollars,” she said. “I’m blown away.”

Curaleaf, the new owner, didn’t respond to a request for comment about Cura’s past. Current and former Cura executives declined to comment on the company’s history, hiring a reputation management firm, Sard Verbinnen & Co., to field questions.

In a written statement, Sard Verbinnen asserted the marijuana business was separate from Iris and blamed the problems on the investment manager now in prison.

“Despite a years-long, court supervised receivership and a criminal investigation and guilty plea, nobody has ever accused (Cura) investors of having done anything wrong,” the firm said. It declined to answer additional questions.

***

Cura’s tale is a complex, multi-act drama. To understand what happened go back to 2015, the year recreational marijuana became legal in Oregon.

At that time Iris Capital was coming apart. Prosecutors say the company’s founder, a financial manager named Shayne Kniss, was abusing alcohol and using investors’ money for his own entertainment – at restaurants, bars, grocery stores, on pet care, vacations, at Nordstrom and at Frederick’s of Hollywood.

Additionally, prosecutors say he embezzled $529,000 of his clients’ money to invest in his marijuana business, which went by various names before finally settling on Cura.

Back then the marijuana industry seemed wide open and hundreds of entrepreneurs, from small-time growers to neighborhood retailers, wanted to get in on the ground floor. The gold rush mentality contributed to massive oversupply, which sent prices plummeting and put many of the upstarts out of business.

Cura, though, found a lucrative niche. It sells wholesale cannabis oil used in vaping cartridges to retailers under the brand name Select Oils.

Vaping has surged in popularity and Cura became the supplier for many of the best-known cannabis brands. Cura sells oils under its own Select name for vaping. It also sells Select brand cannabidiol, CBD, which doesn’t include THC, the agent that produces the high associated with smoking pot.

In Portland, you can pick up Select CBD in the health aisle at New Seasons in flavors including lavender, lemon-ginger and peppermint for $60. Or you can buy a Select muscle rub derived from hemp, or CBDs for pets in chicken, bacon or salmon flavors for $48 per bottle.

Long before Wednesday’s $1 billion deal, Cura was among the nation’s most celebrated marijuana companies. It reported $117 million in sales last year, nearly triple its revenue from the prior year and claimed to have raised $115 million.

One of Oregon’s biggest startups in a generation, Cura has hired executives from Columbia Sportswear, Apple and La Quinta Inns. The company said it wanted to be “the Nike of cannabis.”

Business Insider and The New York Times heralded the business. The Portland Business Journal called it

Oregon’s fastest-growing company. Willamette Week anointed its current CEO “

The Unicorn,” a Silicon Valley term for startups that come out of nowhere to achieve a market value of $1 billion.

The seeds of that success were planted at Iris Capital, as Kniss quietly took clients’ money for the marijuana business as his real estate investments fell apart.

The roots of Cura Cannabis

• 2010: Lake Oswego financial advisor Shayne Kniss founds Iris Capital; raises money from 2011 to 2013.

• 2014: Portland tech investor Nitin Khanna settles sexual assault lawsuit brought against him by wife’s hairdresser.

• 2015: Recreational marijuana becomes legal in Oregon. Amid mounting financial woes, Kniss shutters Iris Capital and goes to work full time on a marijuana business called Terwilliger Partners.

• July 2015: Nitin Khanna becomes CEO of Terwilliger. Solicits investments valuing the marijuana business at up to $17 million.

• November 2015: Judge appoints receiver to take control of Iris, recover any funds for investors; Kniss gives up control of Iris as part of deal with state financial regulators.

• March 2016: Khanna and his brother agree to buy Terwilliger from the Iris estate for $519,000.

• 2017: Terwilliger changes its name to Cura Cannabis, expands into California and Nevada after those states vote to legalize recreational marijuana.

• May 2018: Kniss pleads guilty to wire fraud. Khanna steps down as Cura’s CEO after anonymous social media accounts revive 2012 rape allegations. Cura sues in hopes of learning the identities of the people behind the social media accounts.

• November 2018: Cura says it raised $75 million, on top of a $45 million investment in May. The company says it has raised $125 million total and that 2018 sales will top $120 million.

• January 2019: Cura sues California rival Bloom Farms, alleging it publicized Khanna’s past to hurt Cura’s sales.

• February 2019: Kniss sentenced to three years in prison for wire fraud related to the Iris scandal. He began serving his sentence in April.

• May 2019: Cura sells to a Massachusetts company, Curaleaf Holdings, in an all-stock deal valued at roughly $1 billion.

Some investors say Kniss approached them about moving their real estate investment to the marijuana business but that they refused. Others say he kept them in the dark and they didn’t find out until lawyers and accountants got involved to untangle the mess.

“I just about swallowed my tongue,” one retiree said. “I just thought, for Pete’s sake, (Kniss) never asked me about it.”

That 70-year-old investor asked that she not be named because of the embarrassment associated with being the victim of a financial scam. She said she had known Kniss for several years before investing in what she believed to be a legitimate real estate business. She said she knew nothing of Kniss’ marijuana investments until prosecutors contacted her amid the firm’s collapse.

“I didn’t have any knowledge of any of it. It was all new to me,” she said. “It was like going down a rabbit hole. What’s next? Like Alice.”

After the money disappeared

, the woman said, she spent months living day-to-day, selling jewelry and anything else she could think of to pay her bills and cover her mortgage.

“It was devastating,” she said. “Because I worked for 34 years presuming I was doing the right thing, saving my money and preparing for retirement.”

Court records show the real estate and marijuana business were closely entwined, sharing offices and the same founder, Kniss, who moved money from both between their bank accounts.

While Kniss is in prison in Georgia, no one else was charged in the scandal. Dozens of victims remain out roughly $1 million altogether. They say their real losses are much greater than that because they missed out on the opportunity to earn returns on their money during the years it was tied up in Iris.

“Wouldn’t it be wonderful if they decided to give everybody all their money back, if they’ve got all that dough?” she asked, before Wednesdays’ $1 billion deal. She said the scam that cost her $320,000 of the $800,000 she invested in Iris when she cashed out her pension.

***

Cura’s rise contrasts sharply with Iris’ decline.

The cannabis company emerged from the Iris wreckage courtesy of former Portland tech entrepreneur Nitin Khanna.

An American-educated immigrant from India, Khanna, 48, became wealthy in 2007 when he sold an Oregon software company he co-founded, Saber Corp., for $420 million. He subsequently became Portland’s most prominent tech investor, backing several small companies and starting a boutique investment bank to help the city’s entrepreneurs cash out.

Nikin Khanna in 2017.

That all came apart in 2014 when a woman accused Khanna of raping her in the early hours on the morning of his own wedding in 2012. The woman, hired as a hairdresser for the bride, said Khanna attacked her when she came to his hotel room door in Newberg looking for a friend of his.

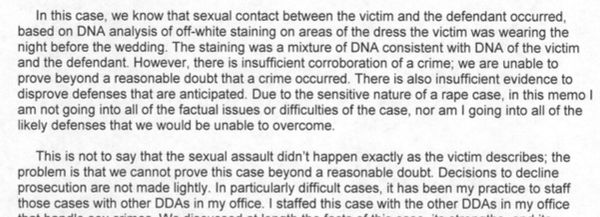

Khanna denied the accusations and reached a civil settlement with the woman, terms of which were never disclosed. Yamhill County prosecutors opted not to charge Khanna. They said DNA tests proved he had sexual contact with the hairdresser but prosecutors concluded they couldn’t demonstrate it was not consensual.

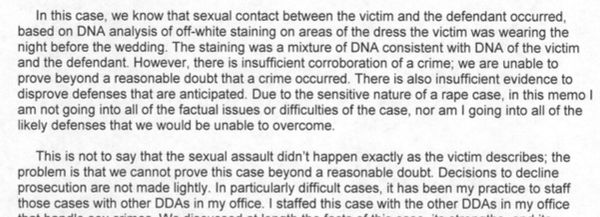

"That is not to say that the sexual assault didn't happen exactly as the victim describes," county prosecutors wrote in a memo explaining their decision. "The problem we have is that we cannot prove this case beyond a reasonable doubt."

Excerpt from the Yamhill County prosecutors' memo regarding rape allegations against Nitin Khanna.

Afterwards, Khanna withdrew from the socially conscious Portland tech scene and started over, this time in marijuana.

***

As Kniss shifted from real estate to pot, he met Khanna at an industry event and they bonded over their shared ambitions for the recreational marijuana market. Soon, they went into business together with Khanna as CEO of the marijuana company -- even as prosecutors began to zero in on the real estate scam.

After Iris’ collapse, the Multnomah County Circuit Court appointed a receiver to untangle the remains of the real estate business and recover whatever was left for the victims of the scheme.

Records show a firm owned by Khanna and his brother paid $519,000 to settle legal claims and buy Kniss’ cannabis business, then known as Terwilliger Partners, out of receivership. Ultimately, that money helped repay some of the $5 million that investors lost in Iris’ collapse.

Amy Mitchell, the court-appointed receiver in charge of the Iris estate, said confidentiality rules preclude her from discussing the agreement to sell the marijuana business that became Cura to the Khanna brothers.

Court filings show that she reviewed the marijuana business’ financial results in 2016 and concluded the company would generate no more than $350,000 through liquidation – and that Iris’ real estate investors might not get all that money because the separate marijuana investors might have a claim, too.

That’s a far cry from the billion dollars Cura sold for Wednesday, but Mitchell wrote that she believed the cannabis business might simply dissolve if she tried to wring more from it.

Cura representatives note that investors signed off on the settlement for the marijuana business and never challenged it. Further, the company says that the money the Khannas paid for the business was the first restitution Iris’ victims received.

By that time, though, court and regulatory filings show the cannabis business had raised hundreds of thousands of dollars from other investors. Those investors may have valued the company differently than a court-appointed receiver, gauging market prospects and brand value over tangible assets.

Records show some of the startup investors valued the marijuana business at up to $17 million -- 30 times more than what the Khannas paid to extricate it from the Iris debacle. When The Oregonian/OregonLive asked about Cura’s ties to Iris in 2016, Khanna said he had

no knowledge of the real estate scam.

Cura Cannabis: Cast of Characters

Shayne Kniss, age 43: Veteran financial manager, Kniss started the real estate investment firm Iris Capital and raised $4.3 million from 47 investors, then began diverting funds to a marijuana startup when real estate returns didn’t meet projections. He pleaded guilty in 2018 to wire fraud; prosecutors accused him of embezzling more than $500,000 – some of which he diverted to the marijuana business, first known as Terwilliger Partners and later as Cura Cannabis. Sentenced to three years in federal prison, he began serving his term last month.

Nitin Khanna, 48: Former Oregon tech entrepreneur and investor, Khanna turned to marijuana after rape allegations – accusations he denied. Khanna became CEO of Terwilliger Partners in 2015 and changed the company’s name to Cura Cannabis in 2017. He left the company in 2018 after social media users highlighted the past rape allegations.

Cameron Forni, 33: Cura’s current CEO, Forni is the son of a wealthy Oregon hospitality executive. He developed a brand of cannabis oils in his apartment and incorporated them into Cura. He replaced Khanna as Cura’s CEO in 2018 and will become Curaleaf’s CEO after its $1 billion acquisition of Cura is final.

Nick Slinde, 44: An attorney for Iris and Cura, Slinde took a 15 percent stake in the marijuana business in exchange for providing legal services to Iris Capital. Kniss accuses him of funneling a $500,000 repayment to Iris from the investment fund’s real estate manager into the marijuana business, in which he held an ownership stake. In a bar complaint, Kniss said that constitutes a conflict of interest.

The cannabis business thrived after its separation from Iris. Khanna became CEO of Terwilliger Partners and changed its name to Cura Cannabis a year later. It soon expanded into the newly legalized marijuana markets in Nevada and California.

During this period, Khanna paired with another cannabis entrepreneur, Cameron Forni, and began marketing their oils under the Select Oil brand. Last year, Forni

described to Willamette Week how he started the business in his Pearl District apartment, recounting that he and his wife maxed out their credit cards while cooking up their oils, which they called Select.

But Cura was already a going concern by that time. And Forni was not the typical starving entrepreneur – he’s the son of wealthy Oregon hotelier Rodney Forni, chief operating officer of Pacific Inns. In 2017, Forni, who is now 33, staged a

lavish wedding for himself and his bride, a professional acrobat, inside the Vatican.

***

Cura says it has more than 500 employees. The Portland company says it raised more than $115 million ahead of Wednesday’s sale, though it won’t identify its investors.

Cura’s growth has brought attention from local, national and cannabis trade publications, which cast it as one of the early successes in the business of legalized marijuana.

Other marijuana businesses signed on to use Cura’s products in their products -- including talk show host Montel Williams’ line of CBD.

The publicity may have backfired, though. Women in the marijuana community quickly discovered the rape allegation against Khanna, which had been widely reported just a few years before when he was a prominent tech investor. They began posting links to old articles last year, demanding accountability from Cura.

In an electronic message to one of the women highlighting the allegations, provided to The Oregonian/OregonLive, Forni claimed he hadn’t known about his business partner’s past.

“I was not aware” of the accusations against Khanna, Forni wrote to one critic last year, until fresh press coverage appeared, triggered by the critics’ social media posts. He complained that his employees were being “attacked and threatened for their lives and neither them nor I had anything to do with it.”

“I got board approval today to remove Nitin,” Forni wrote in a private message to one woman last June. In conjunction with Wedneday’s sale, Forni will now be Curaleaf’s president.

Publicly, Cura said Khanna had stepped down voluntarily. The company won’t say whether he remains one of its major shareholders or if he retained a position on its board of directors. And just as Khanna left the CEO job, Cura began a vigorous legal campaign to defend the company and his reputation. Rather than silence the critics, the aggressive legal strategy attracted widespread media coverage revisiting the original accusations against Khanna.

Cura sued anonymous social media users, seeking subpoenas of Google, Instagram, Twitter, Comcast, Sprint and others to learn who was behind some of the accounts that had highlighted the past accusations. The Portland company also subpoenaed some of the women who had posted links to past articles about the allegations against Khanna, seeking their phone records, emails and access to their social networking accounts.

“In my own personal view I think that it was to try and silence and scare me into being quiet,” said Leighana Martindale, a Portland writer who has published in various cannabis publications and produces events for the industry.

Cura pulled Martindale and others into depositions, for which they incurred thousands of dollars in attorney fees to explain why they posted links to news articles recounting the accusations against Khanna.

“Because I do have a strong voice in the cannabis community I think they wanted to hold me accountable for speaking out,” Martindale said.

In January,

Cura dropped its lawsuit against the social media posters and filed a new complaint against a California rival, Bloom Farms. The Portland company asserted that Bloom was responsible for highlighting Khanna’s past, part of a campaign “to harm Cura’s ability to fundraise, and to reduce competition in the cannabis industry.”

***

Meanwhile, Cura has continued to try to separate itself from its past, highlighting “a proven track record of giving back to non-profits that help women, families and veterans.”

The women who first highlighted the accusations against Khanna aren’t persuaded. They note that 10 months after his ouster, Cura is continuing to wage a legal campaign to defend the company and Khanna’s reputation. Court documents show Nitin Khanna is participating in Cura’s legal case against its critics.

Jennifer Skog, a California publisher who runs a cannabis-focused magazine called MJ Lifestyle, said many people in the marijuana business assume Cura has put its issues with Khanna behind it. She doesn’t see it that way.

“It’s just not a good company,” Skog said. “I could have forgiven them had they gotten rid of him. But they didn’t. Instead they said, basically, we support him.”

News of Cura’s billion-dollar sale Wednesday left her “disgusted,” Skog said. To her, the depositions and subpoenas aimed at the critics who highlighted the accusations are evidence Cura has yet to come to terms with its controversies and is instead trying “to make women scared.”

“I’m just not interested in any sort of misogynistic businesses,” she said, “that are going to be treating women that way.”

Cura Cannabis attorney faces bar complaint

The

tangled heritage of Cura Cannabis now includes a bar complaint against a Portland lawyer who represented the marijuana company from its earliest days and became one of its first shareholders.

In 2014, Nick Slinde took a 15 percent ownership stake in Cura’s predecessor in exchange for doing legal work for Iris Capital, the real estate scam that spawned Cura.

When Shayne Kniss, who founded both companies, was sentenced for wire fraud in March, Kniss’ defense attorney alleged that Slinde made an “astonishing” agreement to settle a dispute between Iris and its former real estate manager who allegedly owed money to the investment firm.

Instead of sending the money to Iris – and potentially, its investors -- the deal put $500,000 into the marijuana business in which Slinde was now part owner, the defense attorney’s memo said. Kniss’ lawyer said Slinde asserted that the investment in a profitable marijuana business could be used to generate funds to repay Iris investors.

Last month, shortly before Kniss began serving his three-year sentence at a federal prison in Georgia, he filed a complaint against Slinde with the Oregon State Bar. Kniss alleged Slinde was engaged in “a significant conflict of interest” by negotiating the agreement on behalf of Iris and then putting the $500,000 repayment in the marijuana business.

In a response to the bar, an attorney for Slinde said that Kniss had signed a waiver acknowledging the potential conflict of interest. Slinde’s response also said that Kniss arranged the deal with his real estate manager long before Slinde got involved.

Court records, though, show Slinde suggesting to Kniss that the two of them can make the real estate manager “find the solution for the (real estate) and (marijuana) businesses.” Another Slinde email shows “the repayment of the $500k he’s putting into MJ,” a reference to marijuana.

State marijuana registration documents show Slinde and his legal partner Phil Nelson owned 15 percent of Cura as late as the fall of 2017.