Well, as you would expect...cronyism and the fight for a spot at the trough is alive and well in the cannabis industry. What else is new?

Tactics scrutinized in Phoenix medical-marijuana dispensary cases

Zoning battles over medical-marijuana facilities in Phoenix have raised questions about the winning group's tactics in an industry where millions of dollars are at stake.

The controversy also spotlights the Phoenix Board of Adjustment, an obscure volunteer board that decided matters for the city.

In recent months, when individuals from the group represented a medical-marijuana dispensary, the Phoenix Board of Adjustment granted the needed approvals to open.

When the same group opposed medical-marijuana facilities, the board denied approval.

ACCUSATIONS DETAILED: Allegations outlined in marijuana-dispensary cases

The group consists of two former city staffers, a prominent Phoenix attorney and a fourth individual from a politically connected family. Those who agreed to speak with

The Arizona Republic said they got involved out of genuine concern for the community.

Attorneys who represented the group's opponents in the cases believe otherwise. They contend members of the group created bogus victims and collected fake signatures for petitions.

Attorneys for Withey Morris, a law firm representing another medical-marijuana dispensary with a case scheduled to go before the board May 11, submitted a memo to the city in late April that detailed the "unusual circumstances" and patterns seen in multiple medical-marijuana appeals.

Citing one case, the memo alleged it "was mysteriously appealed by a sham appellant that is paid for by a Phoenix lobbyist, presumably at the direction of another competitor to chase away competition."

Other zoning attorneys raised similar concerns.

A week after Withey Morris filed its memo with the city, the City Council replaced a majority of the Board of Adjustment's members with little explanation.

The motivations behind the questionable behaviors are unclear.

The attorneys have offered no proof of involvement by a competitor.

The lobbyists and activists in question denied the allegations, saying they were not paid by a marijuana competitor.

Board of Adjustment members, by city rules, cannot answer questions about their decisions in specific cases.

And Mayor Greg Stanton, who recommended the board members be replaced, did not answer a specific question about whether his decision was related to the medical-marijuana allegations.

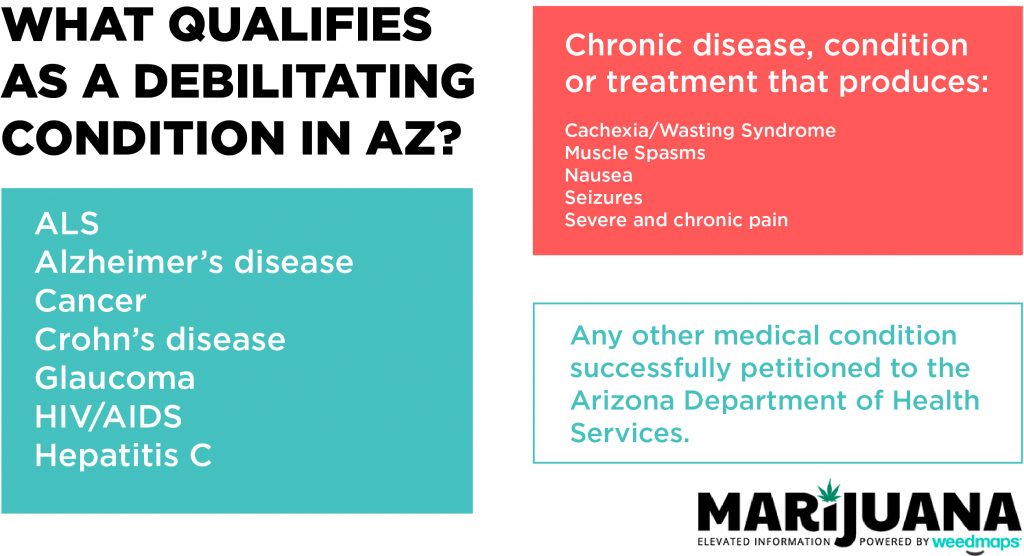

Twenty-nine states and Washington D.C, have legalized the use of medical marijuana and on top of that, nine states have legalized recreational pot. But the question is, why was it illegal in the first place? Just the FAQs

How marijuana approvals work

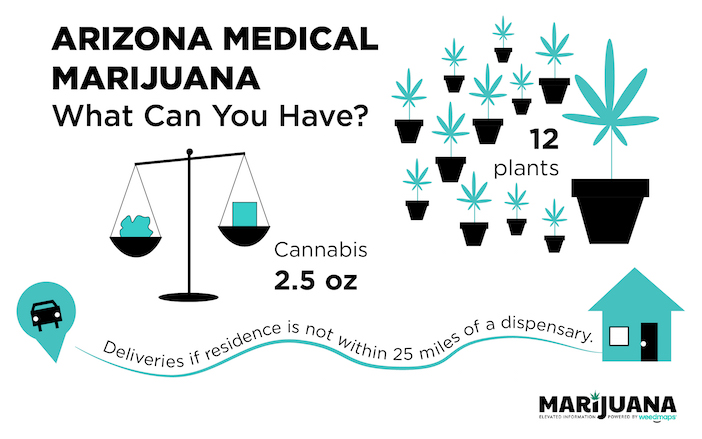

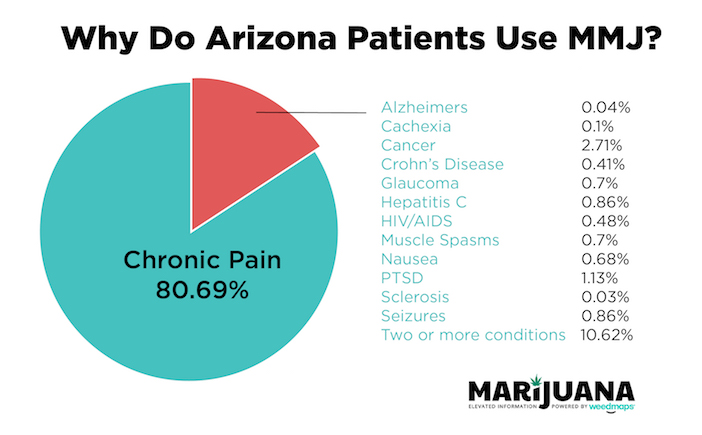

Arizona voters legalized medical marijuana in 2010 and the industry has boomed. Medical-marijuana sales

increased by nearly 50 percent last year over the prior year, with an estimated value of $387 million — and show no signs of slowing down.

State and local regulations limit how many dispensaries can operate and where, making the medical-marijuana industry one of the most competitive businesses in Arizona, according to zoning attorneys and people familiar with the industry.

When a business wants to open a dispensary or add a cultivation center in Phoenix, it must get a special-use permit from the city.

The business must also secure additional approvals if the proposed location is within a certain distance of another medical-marijuana facility, a school, a church, a community center or a handful of other places.

Representatives of the proposed medical-marijuana facility must state their case at a public hearing in a small room on the ground floor of City Hall. A hearing officer decides whether the request meets the city's standards.

If the hearing officer denies the request, the medical-marijuana dispensary can appeal.

If the request is approved, anyone who opposes the facility can appeal.

Those appeals are sent for a final decision to the Board of Adjustment, composed of volunteers appointed by the mayor and City Council members.

Visitors enter Phoenix City Hall through the southwest doors at 200 W. Washington St. (Photo: Mark Henle/The Republic)

Similar appeals, similar people, similar results

Since March, the Board of Adjustment has heard three medical-marijuana facility appeals. It overturned the hearing officer's decision in each case.

Two of those appeals, and one scheduled for May 11, were filed by people claiming to live or own property nearby who were disgruntled with the hearing officer's decision to approve the facilities. All three proposed facilities were in west Phoenix, but miles apart.

The other appeal came from a medical-marijuana business after a hearing officer denied its requests for a dispensary in north-central Phoenix.

A combination of four people kept appearing in these cases: Phoenix lobbyists Joe Villasenor and Layla Ressler, west Phoenix resident Alexia Nunez and zoning attorney Nick Wood.

Villasenor paid for two of the neighborhood-initiated appeals and provided community outreach on the other. He said he paid the $2,760 filing fee for each of the neighbors' appeals out of concern for the community.

A city staffer wrote in an email that Villasenor also submitted the appeal for the dispensary-initiated appeal, but Villasenor denies that.

Ressler paid for one of the neighborhood-initiated appeals on behalf of her uncle, who owns a business near a proposed medical-marijuana facility. She said she also provided pro bono community support for one of the appeals Villasenor paid for.

Nunez gathered petitions for two of the appeals, and her phone number was listed as the primary contact number for the appellant on the two other appeals.

Wood represented all three appellants in the neighborhood-initiated appeals, although Wood later backed out of one of the cases because of a conflict. He did not return requests for comment.

Neighborhood-initiated appeals

According to state law, only a "person aggrieved" can file an appeal. The Board of Adjustment decides who qualifies as a "person aggrieved," but typically the person must live or own property nearby.

All three of the neighbor-initiated appeals contained nearly identical language describing why the facilities should be denied. Two of the three appellants do not appear to live at the addresses they provided on the appeal paperwork, and the appeal forms also included incorrect phone numbers,

The Arizona Republic found.

Villasenor said he gave each appellant a copy of sample language to use, and each used it verbatim.

"I mean, that's just the fastest thing to do," he said.

In the three cases that neighbors appealed, lawyers representing the proposed medical-marijuana facilities provided the Board of Adjustment with evidence of what they called fraud, forgery or deceit by the appellants or their representatives. The attorneys questioned the validity of petition signatures and the legitimacy of the appellants.

But the board sided with the appellants in the two appeals that have come before it, overturning the hearing officers' recommendations.

Dispensary-initiated appeal

In the final case, Nunez went to work for a dispensary, defending it against opposition from neighbors.

The proposed dispensary hired Nunez to collect signatures of support. Nearby residents who opposed the dispensary and their attorney alleged to the board that those signatures were fake.

Despite neighborhood opposition and allegations of phony signatures, the Board of Adjustment overturned the hearing officer's decision, clearing the way for the dispensary to open.

According to an email from a city staff member, Villasenor submitted the appeal paperwork on behalf of the dispensary.

Villasenor denies he was involved. He said he just ran into the person who submitted the appeal while he was at City Hall.

Plants in a grow room at a marijuana farm supplying Arizona's medical-marijuana industry. (Photo: David Wallace/The Republic)

The two former staffers: Villasenor, Ressler

Villasenor and Ressler have long histories with the city.

Villasenor was a top aide to former Mayor Phil Gordon until 2010. Ressler was Councilman Michael Nowakowski's chief of staff until 2016. She also served as Councilman Sal DiCiccio's fundraiser during his 2017 campaign.

Villasenor, Ressler and their families are steady donors in city elections. They have donated to the campaigns of nearly all of the current council members.

Villasenor and Ressler were involved in a controversial land deal in 2016 involving Nowakowski and his private-sector employer, which

prompted an Attorney General's Office investigation. Prosecutors did not find sufficient evidence to bring charges under the state's conflict-of-interest laws.

In 2017,

The Arizona Republic found that Villasenor had not registered as a lobbyist in Phoenix although he was acting as a lobbyist on several development deals, an apparent

violation of city lobbying-disclosure rules.

His attorney contended Villasenor did register but the documents were somehow lost or the city clerk didn't properly log them.

Villasenor and Ressler previously were engaged to be married and are still in a relationship, Villasenor said. They each own companies that perform community-outreach services.

The petition gatherer: Nunez

Nunez only recently began attending Phoenix meetings, but her family has a long history in politics. She is the granddaughter of West Valley minister and unsuccessful state Legislature and congressional candidate Eve Nunez.

Nunez has provided different information about herself at three city hearings and meetings since December.

In one hearing, she said she was a chaplain, mentor, caseworker and counselor for an organization run by her family called Hope4Teenz. At another, she said she owned a company called Urban Petitions. Most recently, she appeared before a City Council subcommittee as a "long-term resident of the West Valley" who was opposed to medical marijuana near libraries.

The fake-signature allegations made by opposing attorneys at recent Board of Adjustment meetings are not the first ones Nunez has faced.

In 2009, she was arrested after attempting to cash a check for nearly $1,000, according to court records. When the bank contacted the person who made out the check, the person said she had written the check for $31.66.

Nunez told police a co-worker had altered the check and they had planned to split the profits. She pleaded guilty to criminal possession of a forgery device.

Three years later, police arrested Nunez after she attempted to use a credit-card machine at a hotel where she worked to divert $20,000 to her personal bank account, according to court records.

Nunez pleaded guilty to a fraudulent schemes and artifices charge.

Nunez initially agreed to speak with

The Republic, then canceled because of "a very important family matter" and referred questions to her attorney.

Her attorney, Alexander Kolodin, said Nunez "categorically denies any accusations of forgery." He did not answer 16 specific questions sent to him by email.

'Sham appellant' covering for a competitor?

Multiple attorneys who represented the denied medical-marijuana dispensaries told the Board of Adjustment about the similarities in the appeals and questioned whether one individual or entity — perhaps a competitor dispensary — is behind all of them.

"When looking at this application and appellant, nothing has been clear to us as to who our actual opposition is," attorney Lindsay Schube said at the board's March meeting.

"There is a very, very odd ... kind of commingling between three separate cases and literally the three applications that are before you have identical language … and they are all paid for by either Miss Layla Ressler or Mr. Joe Villasenor," attorney Ben Graff said minutes later at the same meeting.

The memo from Withey Morris, filed by the dispensary with the case scheduled to go before the board on May 11, also alleged Villasenor violated Phoenix lobbying rules by paying for the appeals but failing to disclose his client.

Phoenix lobbying rules require lobbyists to register and disclose all clients. Villasenor is registered, but his only listed client is his own company — Sovereign Land Assets.

Villasenor said he did not have a client because he assisted in these cases pro bono.

Allegations denied

In denying the allegations made against them, Villasenor and Ressler point back at the attorneys, accusing them of trying to intimidate opposition and circumvent the public process.

Villasenor said he got involved and paid for two of the appeals after the Nunez family contacted him with neighborhood concerns about the medical-marijuana facilities.

Ressler said her uncle asked her to represent him on the other appeal because he owns a business nearby.

Villasenor and Ressler both said they were not paid by a marijuana competitor to oppose the medical-marijuana facilities, although Villasenor said he has been paid to oppose a dispensary for a competitor in the past.

Villasenor said he filed a complaint against Graff, one of the dispensary attorneys, with the State Bar of Arizona, accusing Graff of lying and making false statements about him and others. Ressler provided a copy of the complaint to

The Republic, but a spokesman from the state Bar said there is no record of Villasenor filing such a complaint.

Graff said he was unaware of the complaint until provided a copy by

The Republic.

"I stand behind every statement I made to the Board of Adjustment in the representation of my client," Graff said. "The allegations made in the draft Bar complaint are demonstrably false and a clear attempt to alter the facts and undisputed evidence."

Enough community outreach?

Ressler and Villasenor said they got involved in the appeals because the medical-marijuana dispensaries had not done enough public outreach to educate the community — something both of them do for a living.

Ressler said that although the dispensaries sent out information to nearby businesses and residents, they didn't host community meetings or go door to door to make sure everyone understood what they were planning to bring to the community.

"If you want to be a good community player and a good community partner, that's what you do. And again, I just go back to my basic value that the voice of the community is important. And our process has been developed for the community to be involved," she said.

During the appeals, Villasenor and Ressler brought up concerns about the proximity of the proposed medical-marijuana facilities to churches and libraries.

Phoenix's medical-marijuana ordinances require that a dispensary or cultivation center acquire special approval if it locates within 1,320 feet from a place of worship.

But most of the churches that Villasenor discussed during the hearings were not legally established with the city. They did not have a proper certificate of occupancy.

Phoenix Planning Director Alan Stephenson said a church must have a certificate of occupancy to qualify for the spacing requirement from a medical-marijuana facility.

Some members of the Board of Adjustment appeared sympathetic to the non-legally established churches, however, and the board voted to overturn the hearing officer's decision in favor of the churches and other community opposition.

Ressler and Villasenor also said they were concerned about one of the dispensaries' proximity to Desert Sage Library, in the case scheduled for May 11. The ordinance also requires special approval if a dispensary locates within 1,320 feet from a "public community center."

Ressler and Villasenor say they believe Desert Sage Library, and all libraries, should qualify as "public community centers."

They don't, Stephenson said. The city went through a long public process to adopt its current medical-marijuana spacing requirements, and libraries were never mentioned, he said. It would be inappropriate to say libraries qualify now since there was never public input on that topic, he said.

Board of Adjustment shake-up

Days after the Withey Morris memo was submitted to the city — and the allegations it contained became public — Mayor Greg Stanton asked for the replacement of four of the seven Board of Adjustment members.

Phoenix Mayor Greg Stanton (Photo: Tom Tingle/The Republic)

Three of their terms had expired and another wished to resign from the board, according to city staff members.

“I believe it became time for new leadership on the board, and that time will show the Council did the right thing," Stanton said in a statement.

The request went before the City Council a week later. Although Stanton did not say why he wanted to replace the board members, some of the other council members linked the change to the Withey Morris memo and other allegations.

Councilman Sal DiCiccio tried — but failed — to get the item delayed to a future meeting.

"There's an innuendo around this board that they've done things wrong ... this is the first time that I've ever seen a citizens group collectively being attacked by a law firm in the city of Phoenix," DiCiccio said at the meeting.

Board of Adjustment members Emilio Gaynor, Yvonne Hunter and Steve Beuerlein voted in favor of the opposition in both of the appeals where Villasenor and his associates assisted with the opposition. Talonya Adams voted in favor of one of those appeals but left the meeting before casting a vote in the second.

All four board members voted in favor of the facility in the case where Nunez worked for the dispensary.

Stanton replaced Adams, Gaynor and Hunter along with Pam Koester, who told city staff she wanted to resign from the board.

Adams, Gaynor and Hunter said they were not permitted per city rules to answer questions about their decisions in specific cases. However, Adams and Hunter said that all cases are different and can't be compared with one another.

Adams, the former board chairwoman, said she learned of her replacement less than a week before the board's next scheduled meeting and did not receive an explanation.

Asked if she thought her removal was tied to the medical-marijuana appeal controversy, she said she didn't know.

"I would hope ... that there is not a nexus between a manner in which a board member votes and their ability to continue to serve. That would be concerning to me," Adams said.