|

Sponsored by |

|---|

|

|

|

-

Need help navigating the forum? Find out how to use our features here.

-

Did you know we have lots of smilies for you to use?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Lunacy I didn't know that!

- Thread starter CarolKing

- Start date

Mummy Brown paint pigment was made of real mummies

Believe it or not, there used to be a color pigment known as Mummy Brown. To your surprise — or revulsion — the pigment production relied on using real mummies, both human and feline, dug out from ancient Egyptian sites. Other names used for the color included Caput motum and Egyptian brown.

For a few centuries, this usage of mummies persisted; Mummy Brown was a well-loved pigment among a number of pre-Raphaelite painters. Tubes containing the color were being sold as recently as the 1960s.

To produce the paint, ground-up remains of mummies were mixed with white pitch and myrrh, according to the Journal of Art in Society. The result was an alluring, transparent brown hue, something between raw and burnt umber tone.

Martin Drolling’s Interior of a Kitchen made extensive use of mummy brown

Although it was prone to fading, a number of painters including Eugène Delacroix, Martin Drolling, and Edward Burnes were keen on painting with it. Little did they know they were “resurrecting” the dead in their art studios along the way.

The practice of making color pigment from mummies probably originated from another equally bizarre practice. In Europe, ground mummy was also a prized additive in medicine. People would swallow or topically apply a variety of mummy-based remedies to aid an array of aliments.

When ancient Egyptians prepared their dearly departed for the afterlife, they used various products to embalm and preserve the body — these included beeswax, resins, spices and sawdust.

Bitumen, a thick, black and oily substance which supposedly provided the brownish tan of the mummy, was another key ingredient in the preservation process. Its Arabic name was mummiya. One reason why mummies were valued in medicine could have been the wrongful assumption people had about bitumen: that it had healing properties.

More than that, people also believed there was an inexplicable, otherworldly life force in mummies. Consumption of mummies, the reasoning followed, would restore the human body to full health. Such claims were backed by famous names of the day, such as Paracelsus, a German-Swiss physician and alchemist who redefined 16th century medicine — and doubtless made a healthy profit from supplying his mummy-based cures.

And indeed, during the 16th and 17th centuries healing powders from ground mummies became a fairly available “drug” around Europe, prescribed for many things including headaches and sores.

After some time, the demand for mummies in medicine thankfully went out of fashion, but Napoleon’s campaign to Egypt from 1798 to 1801 announced the beginning of yet another craze about anything Egypt. Now it was time for art to benefit from mummies…among other things.

Mummies became so increasingly popular again that “tourists brought entire mummies home to display in their living rooms, and mummy unwrapping parties became popular,” according to the National Geographic

Although attempts were made to ban imports of mummies, many were still shipped across the Mediterranean. They were “brought over from Egypt to serve as fuel for steam engines and fertilizer for crops, and as art supplies.”

Not all artists who used Mummy Brown knew they were using a color made up of people who had lived and died thousands of years before them. Some of those artists got pretty upset when they were updated about the pigment’s contents and were quick to put a halt on any usage of the color.

Edward Burnes opted to bury the tube of Mummy Brown. A statement given by his wife, Georgina, recollecting how he found out the vicious truth about the pigment is widely cited:

“Edward scouted [scornfully rejected] the idea of the pigment having anything to do with a mummy — said the name must be only borrowed to describe a particular shade of brown — but when assured that it was actually compounded of real mummy he left us at once, hastened to the studio, and returning with the only tube he had, insisted on our giving it decent burial there and then.”

As word spread, more and more people began to realize what wrongdoing was being done here and how this undermined the study of ancient Egyptian civilization. Real Mummy Brown disappeared from color palettes. Tubes tagged as mummy brown can be found today, but — we hope — they do not contain any mummified remains.

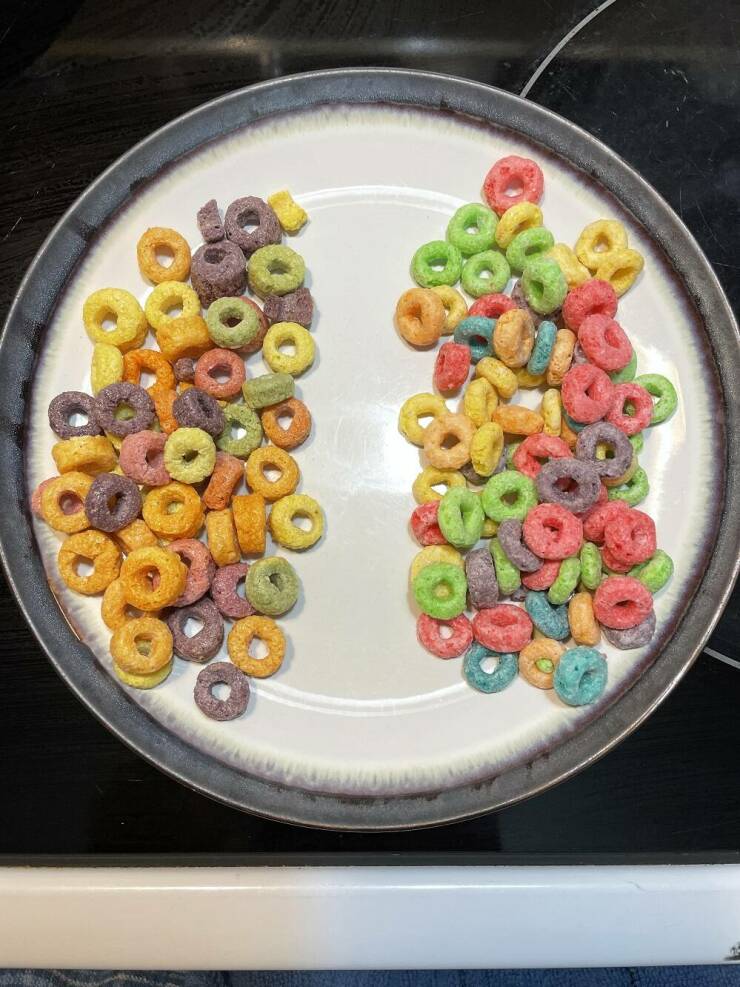

Fruit Loops in the U.S. are different colors than the Fruit Loops in Canada....

bulllee

Well-Known Member

A Student Proved Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Possible

Caroline Delbert - Yesterday 10:46 AM

© artpartner-images - Getty ImagesA college student has mathematically proven the physical feasibility of paradox-free time travel. Does this mean we can all go back to 2019?

- Time travel is deterministic and locally free, a paper says—resolving an age-old paradox.

- This follows recent research observing that the present is not changed by a time-traveling qubit.

- It's still not very nice to step on butterflies, though.

University of Queensland student Germain Tobar, who the university’s press release calls “prodigious,” worked with UQ physics professor Fabio Costa on this paper. In“Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice,” Tobar and Costa say they’ve found a middle ground in mathematics that solves a major logical paradox in one model of time travel. Let’s dig in.

The math itself is complex, but it boils down to something fairly simple. Time travel discussion focuses on closed time-like curves (CTCs), something Albert Einstein first posited. And Tobar and Costa say that as long as just two pieces of an entire scenario within a CTC are still in “causal order” when you leave, the rest is subject to local free will.

“Our results show that CTCs are not only compatible with determinism and with the local 'free choice' of operations, but also with a rich and diverse range of scenarios and dynamical processes,” their paper concludes.

In a university statement, Costa illustrates the science with an analogy:

“Say you travelled in time, in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus. However if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place. This is a paradox, an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe. [L]ogically it's hard to accept because that would affect our freedom to make any arbitrary action. It would mean you can time travel, but you cannot do anything that would cause a paradox to occur."“Say you travelled in time, in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus. However if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place. This is a paradox, an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe. [L]ogically it's hard to accept because that would affect our freedom to make any arbitrary action. It would mean you can time travel, but you cannot do anything that would cause a paradox to occur."

Some outcomes of this are grouped as the“butterfly effect,” which refers to unintended large consequences of small actions. But the real truth, in terms of the mathematical outcomes, is more like another classic parable: the monkey’s paw. Be careful what you wish for, and be careful what you time travel for. Tobar explains in the statement:

“In the coronavirus patient zero example, you might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would. No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you. Try as you might to create a paradox, the events will always adjust themselves, to avoid any inconsistency.”“In the coronavirus patient zero example, you might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would. No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you. Try as you might to create a paradox, the events will always adjust themselves, to avoid any inconsistency.”

While that sounds frustrating for the person trying to prevent a pandemic or kill Hitler, for mathematicians, it helps to smooth a fundamental speed bump in the way we think about time. It also fits with quantum findings from Los Alamos, for example, and the way random walk mathematics behave in one and two dimensions.

At the very least, this research suggests that anyone eventually designing a way to meaningfully travel in time could do so and experiment without an underlying fear of ruining the world—at least not right away.

Kellya86

Herb Gardener.....

Science is fucked up.... when i think of this shit, especially when tripping or really high, it jus winds me up that there is so so much more going on, and we are never gonna get to know.... we all jus live in this universe, going about our day, paying taxes to peadophiles, and it could all just end suddenly at any moment..A Student Proved Paradox-Free Time Travel Is Possible

Caroline Delbert - Yesterday 10:46 AM

© artpartner-images - Getty ImagesA college student has mathematically proven the physical feasibility of paradox-free time travel. Does this mean we can all go back to 2019?

In a peer-reviewed paper, an honors undergraduate student says he has mathematically proven the physical feasibility of a specific kind of time travel. The paper appears in Classical and Quantum Gravity.

- Time travel is deterministic and locally free, a paper says—resolving an age-old paradox.

- This follows recent research observing that the present is not changed by a time-traveling qubit.

- It's still not very nice to step on butterflies, though.

University of Queensland student Germain Tobar, who the university’s press release calls “prodigious,” worked with UQ physics professor Fabio Costa on this paper. In“Reversible dynamics with closed time-like curves and freedom of choice,” Tobar and Costa say they’ve found a middle ground in mathematics that solves a major logical paradox in one model of time travel. Let’s dig in.

The math itself is complex, but it boils down to something fairly simple. Time travel discussion focuses on closed time-like curves (CTCs), something Albert Einstein first posited. And Tobar and Costa say that as long as just two pieces of an entire scenario within a CTC are still in “causal order” when you leave, the rest is subject to local free will.

“Our results show that CTCs are not only compatible with determinism and with the local 'free choice' of operations, but also with a rich and diverse range of scenarios and dynamical processes,” their paper concludes.

In a university statement, Costa illustrates the science with an analogy:

“Say you travelled in time, in an attempt to stop COVID-19's patient zero from being exposed to the virus. However if you stopped that individual from becoming infected, that would eliminate the motivation for you to go back and stop the pandemic in the first place. This is a paradox, an inconsistency that often leads people to think that time travel cannot occur in our universe. [L]ogically it's hard to accept because that would affect our freedom to make any arbitrary action. It would mean you can time travel, but you cannot do anything that would cause a paradox to occur."

Some outcomes of this are grouped as the“butterfly effect,” which refers to unintended large consequences of small actions. But the real truth, in terms of the mathematical outcomes, is more like another classic parable: the monkey’s paw. Be careful what you wish for, and be careful what you time travel for. Tobar explains in the statement:

“In the coronavirus patient zero example, you might try and stop patient zero from becoming infected, but in doing so you would catch the virus and become patient zero, or someone else would. No matter what you did, the salient events would just recalibrate around you. Try as you might to create a paradox, the events will always adjust themselves, to avoid any inconsistency.”

While that sounds frustrating for the person trying to prevent a pandemic or kill Hitler, for mathematicians, it helps to smooth a fundamental speed bump in the way we think about time. It also fits with quantum findings from Los Alamos, for example, and the way random walk mathematics behave in one and two dimensions.

At the very least, this research suggests that anyone eventually designing a way to meaningfully travel in time could do so and experiment without an underlying fear of ruining the world—at least not right away.

And why is everything made of nearly nothing..

And why is everything made of the same 3 things arranged differently...

And why does the universe resemble the very small (quantum level)

The only way to know for sure is some bravery, and a mahusive dose of dmt i think....

If Holly (Ilex aquifolium) finds its leaves are being nibbled by deer, it switches genes on to make them spiky when they regrow. So on taller Holly trees, the upper leaves (which are out of reach) have smooth edges, while the lower leaves are prickly

|

Sponsored by |

|---|

|

|

|