I posted an article (somewhere) a while back that indicated Monsanto was trying to get a patent on cannabis. Leafly has started a series of articles on this....

Leafly investigation: Inside the billion-dollar race to patent cannabis

Patenting cannabis: A four-part Leafly investigation

Part 1, Inside the billion-dollar race to patent cannabis

“You can’t patent a plant, man.”

You may have heard that late one night while passing around a doobie—and it sure sounds right. After all, how could a capitalist enterprise be given legal domain over the DNA of a living being?

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has already issued several patents for specific kinds of cannabis (most recently one for a variety of high-CBD hemp), and for more wide-ranging “utility patents,” but so far they’ve gone unenforced and even unnoticed.

That won’t continue much longer.

In patent law, every week is shark week

Patent protection lawsuits in the agribusiness field have produced some of the nastiest, most expensive litigation battles of the past 20 years. In 2013, a jury ordered DuPont to pay Monsanto $1 billion for infringing Monsanto’s patents for Roundup Ready seeds, which are resistant to the corporation’s weed killer. Monsanto has also famously sued hundreds of small farmers to protect their seed patents. Now biotech and Big Ag are moving in on the cannabis plant.

Today’s legal cannabis market is worth an estimated $11 billion. That could easily double within the next few years. Imagine holding a patent that required every grower of a popular strain to pay the patent holder a licensing fee.

Biotech startups and Big Ag corporations aren’t imagining—they’re planning. With federal legalization looming, some are already filing patent claims on cannabis strains. The bigger players are waiting in the wings, ready to purchase those patents and claim ownership of hugely valuable DNA.

Prepping for the coming patent war

It’s not hard to imagine a Monsanto-fication of commercial cannabis farming.

So over the past few months, Leafly has investigated the state of cannabis biotech and what it portends for the future. What we found was a story—told in four parts—that’s perhaps business as usual in the cutthroat world of corporate agriculture, but represents a massive paradigm shift for traditional cannabis growers.

We start the series with the saga of Phylos Bioscience, a startup company that touted itself as the craft cannabis farmer’s friend—right up until the day founder Mowgli Holmes revealed his master plan.

Ready player one: Mowgli Holmes & Phylos Bioscience

In March 2019, Phylos Bioscience founder Mowgli Holmes stood before a crowd of high-net-worth investors in Miami and prepared to give a sales pitch. Billed as North America’s premier gathering of cannabis capitalists, the annual Benzinga Cannabis Capital Conference brings together entrepreneurs and investors who want to enter the booming industry.

You know the ones I mean: the OG underground heads up in the hills who kept the plant alive through decades of prohibition and now hope to find a toehold in the legal industry.

When Mowgli Holmes founded Phylos in Portland, Oregon, in 2014, those salt-of-the-earth weed farmers were his target demographic. They’re a cagey, distrustful lot, but Holmes steadily won them over with a virtuous story. Phylos, he said, would use cutting-edge technology to safeguard the plant’s incredible genetic diversity, while protecting small-scale growers and breeders from patent trolls and predatory Big Ag corporations.

Above: Phylos founder Mowgli Holmes outlines his vision at the 2017 CannaTech conference.

Creating a ‘galaxy’ of strains

In 2015, Holmes explained his strategy to Cannabis Now:

Strain by strain, Holmes coaxed growers into having their unique heirloom genetics sequenced and added to a publicly accessible database—and pay for the privilege. Phylos’ online portal, dubbed the Galaxy, includes a 3D visualization tool that uses DNA data to map the relationships between thousands of cannabis varieties like constellations in the night sky.

Phylos: the boom years

Investors loved the Phylos story. They pumped more than $14 million into the company between 2014 and 2019.

Farmers and breeders also liked Phylos, and they loved Mowgli Holmes. The company founder’s personal style combined hippie values (he grew up on an Oregon commune) with scientific expertise (he earned a PhD from Columbia University). And his public statements left no doubt where his loyalties lay.

Phylos 2016: ‘We fucking hate Monsanto’

Here’s what Holmes told Vocative in 2016:

“We fucking hate Monsanto. If we can’t find a way to create a craft, artisanal industry, where lots of little people who really lavish love on interesting plants can be involved, and we just get this Anheuser-Busch industry, it’s going to suck.”

Some growers signed up simply because they liked the idea of participating in a scientifically significant exploration of the cannabis plant as a species and wanted to help Holmes fight back against Big Ag. Others joined to establish a “prior art” claim in case of future patent disputes.

Why establishing ‘prior art’ is important

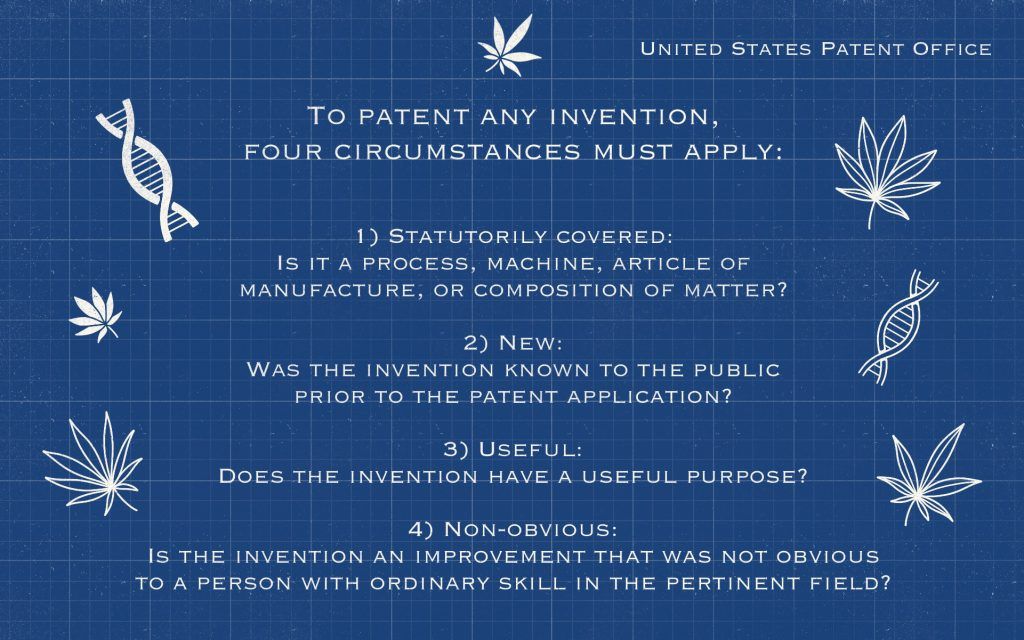

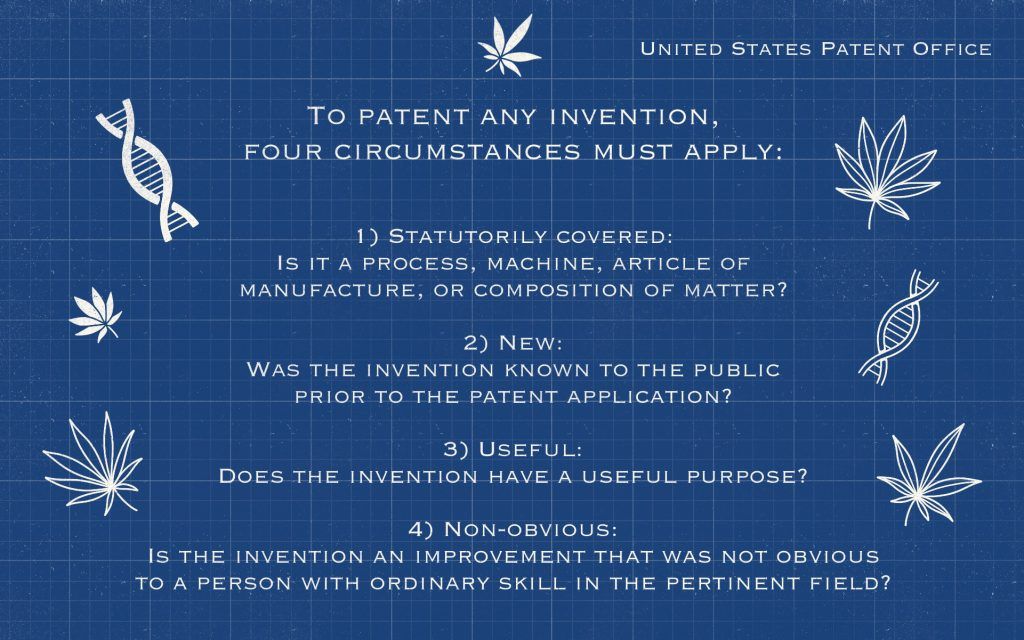

Anyone applying for a patent from the USPTO must prove that their invention is new and non-obvious. The simplest way to reject or invalidate a patent claim is to show what’s known as “prior art”—evidence that the invention was already publicly known or available before the effective filing date of the patent application.

By registering their cannabis strains with Phylos, individual growers and breeders hoped to establish the prior art required to block any future patent claims on those same strains.

The USPTO uses this four-part test to evaluate patent applications. (Gillian Levine for Leafly)

Legal, illegal: patent office doesn’t care

But what about federal law? Cannabis is still a Schedule 1 narcotic according to the US government. So how can you effectively establish “prior art” when the invention in question is illegal?

I contacted the USPTO to find out. They sent the following reply via email:

“The evaluation of prior art for cannabis plant is the same as any other application under review. Extensive search of the prior art in multiple commercial databases are conducted to thoroughly search the claims as compared to what’s already been taught in the public domain. If the strains are already present in the public domain then the claims are evaluated based on the teachings of prior art.”

The USPTO statement also noted that patent applicants are “under duty of candor” to provide anything they know about potential competing claims, and there are also legal means by which members of the public can challenge the validity of an existing patent.

Phylos 2019: They fucking love Monsanto

At the Benzinga investor conference, Holmes at long last pivoted from hippie to capitalist. He opened with a shot at the small farmers who’d trusted him with their prized DNA:

“Compared to how it’s going to be in a few years, [cannabis] kinda sucks right now…”

“In a few years, all the cannabis that’s around right now will be replaced by new, optimized, specialized plants… Our company is developing this next generation of plants, and it’s not going to take very long either.”

Over the past century, Holmes said, “every other major crop has been through an incredibly complex process of plant improvement, for every major important trait.” Only prohibition has kept cannabis out of the Big Ag loop—and that’s about to change, and quickly, because advanced technologies and techniques have vastly sped up the process of breeding.

Then came his big finish.

Bringing Syngenta, DuPont veterans aboard

Holmes name-checked a few members of the Phylos Bioscience Advisory Board, noting that they all have equity in the company. Like Ron Wulfkuhle, who once headed the GMO corn division of agrochemical giant Syngenta. And Barbara Mazur, who recently retired from DuPont Pioneer (“the world’s leading developer and supplier of advanced plant genetics”), where she worked in acquisitions.

“Having these guys around is just critical for us because we’re building a company that’s ultimately going to be acquired by that universe,” Holmes said. “We need to make sure we’re building what they need us to be building.”

Happy 4/20, farmers

On April 16, 2019, about a month after Mowgli Holmes’ Benzinga presentation, and just four days before the annual cannabis holiday of 4/20, Phylos publicly announced that the company would soon begin an in-house cannabis breeding program.

Mz Jill, one of the world’s best known cannabis breeders (she created Agent Orange and Jilly Bean, among others), expressed the outrage felt by a lot of her colleagues. “So, you stole the genetics I paid you to test?” she wrote in an Instagram post. “You told me this wasn’t true!”

No, no no, argued Holmes, including in a 9,000 word interview on the subject.

In an email to Leafly, he made his case more succinctly:

“We didn’t steal our customers’ plants, data, or IP. That data can’t be used for breeding plants, and, when customers gave us permission, we made the data publicly accessible. We’re also not planning to replace all the cannabis out there. We have always been supportive of the craft flower market, and when we do release varieties for that market, they will be open source and available for anyone to breed with. The large-scale market is a different story. Cannabis is not adapted to large-scale cultivation. It needs a lot of work, and it’s our job as a crop science company to develop varieties that really work for that market.”

Former Phylos employee speaks out

Despite these denials, many people reported feeling misled by Mowgli Holmes.

“[Phylos] has chosen to support Big Ag over craft botanists… They had a real, solid chance with one of the most valuable crops on earth as it emerges into full marketplace acceptance to stand with the right people, and change the way the game of agronomics is played. Instead, they took the money. They fucking blew it.”

The Open Cannabis Project closes

Backlash started popping up on social media immediately after the company’s April 16 announcement. It spiked a few days later when somebody began circulating a YouTube video (since taken down) of Holmes speaking in Miami at the Benzinga conference. Soon after, the Open Cannabis Project (OCP) voted to disband itself.

Conceived and created by Phylos ostensibly as “a project to protect heirloom varieties from overbroad patents as cannabis transitions into a legal market,” the OCP issued a statement announcing its own self-immolation, which also included an apology for playing “a key part in shaping Phylos’ public image as altruistic and science-loving protectors of the cultivation community.”

The OCP had already splintered off from Phylos in 2017 to form an independent organization, but the board felt nothing would ever remove the stain from their work.

Next, the Cannabis Classic broke ties with Phylos. Oregon’s premiere cannabis competition and tasting event had previously offered winning entries a free listing in the company’s solar system of strains. Mowgli Holmes had been part of the event’s original thought leadership circle. But no more.

“The bottom line is transparency,” says Steph Barnhart, the Cannabis Classic’s longtime program director. “We took the opportunity to stand beside the farmers we work with, and also to update our own data privacy policies.”

Phylos pushes back

Meanwhile, the angry comments online just kept building. Phylos fired back on Instagram with a lengthy response that was at times evasive, contrite, self-aggrandizing and opaque:

“It’s been suggested that we’re claiming ownership over plant samples that have been sent to us and leveraging our genetic database to compete against our customers. That would be really f*cked up. But it’s not true… We have no claim to any of those plants. And as for bringing dead plant samples back to life, it’s just not possible. And if it was, we wouldn’t do it, because they’re not our plants.”

At first glance, a strong pushback.

Holmes used a variation on the word fuck (just like how he “fucking hates Monsanto”) and flatly denied the allegations. But we’re dealing with a master of double talk. So what exactly is Holmes denying, and more importantly, what is he not denying?

Industry pros not pleased

Seth Crawford is a leading cannabis breeder and co-founder of Oregon CBD, a federally legal cannabis research and development company and CBD-rich hemp seed supplier.

“Mowgli is a brilliant guy,” Crawford says, looking back five years later, “but it was very clear from the outset that he had a specific vision of what was to come, and that was Big Ag moving in and small farmers getting trampled. What set me back in our conversation was that he started playing devil’s advocate, and saying if these small farmers are going to get crushed anyway, why should we try to support them?”

Crawford says from that moment on he has advised people to be wary and not submit their strains to Phylos.

“I just assumed they were trying to scoop up as much data as possible and then get bought out by one of the Big Ag companies that do most of the world’s seed production.”

Next: A mysterious company called Bioscience Institute is patenting cannabis cultivars at an alarming rate. Who really owns the company’s patents?

Leafly investigation: Inside the billion-dollar race to patent cannabis

Patenting cannabis: A four-part Leafly investigation

Part 1, Inside the billion-dollar race to patent cannabis

“You can’t patent a plant, man.”

You may have heard that late one night while passing around a doobie—and it sure sounds right. After all, how could a capitalist enterprise be given legal domain over the DNA of a living being?

As anyone familiar with corporate agribusiness knows, however, it’s not only entirely possible to patent a plant, it’s commonplace. Patents are issued for GMO corn varieties resistant to specific pesticides. Patents cover Honeycrisp apples bred for extra sweetness. Once a plant is patented, nobody can legally grow anything that falls under that patent without acquiring the permission of the patent holder. And that typically requires a fee.Can you really patent a plant? Yes. It's already happening with cannabis strains.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has already issued several patents for specific kinds of cannabis (most recently one for a variety of high-CBD hemp), and for more wide-ranging “utility patents,” but so far they’ve gone unenforced and even unnoticed.

That won’t continue much longer.

In patent law, every week is shark week

Patent protection lawsuits in the agribusiness field have produced some of the nastiest, most expensive litigation battles of the past 20 years. In 2013, a jury ordered DuPont to pay Monsanto $1 billion for infringing Monsanto’s patents for Roundup Ready seeds, which are resistant to the corporation’s weed killer. Monsanto has also famously sued hundreds of small farmers to protect their seed patents. Now biotech and Big Ag are moving in on the cannabis plant.

Today’s legal cannabis market is worth an estimated $11 billion. That could easily double within the next few years. Imagine holding a patent that required every grower of a popular strain to pay the patent holder a licensing fee.

Biotech startups and Big Ag corporations aren’t imagining—they’re planning. With federal legalization looming, some are already filing patent claims on cannabis strains. The bigger players are waiting in the wings, ready to purchase those patents and claim ownership of hugely valuable DNA.

Prepping for the coming patent war

It’s not hard to imagine a Monsanto-fication of commercial cannabis farming.

In fact, several interested parties are already jockeying for that position as federal legalization becomes increasingly likely, and the threat of a massive cannabis patent war looms on the horizon.Several players are already filing patent claims as federal legalization becomes increasingly likely.

So over the past few months, Leafly has investigated the state of cannabis biotech and what it portends for the future. What we found was a story—told in four parts—that’s perhaps business as usual in the cutthroat world of corporate agriculture, but represents a massive paradigm shift for traditional cannabis growers.

We start the series with the saga of Phylos Bioscience, a startup company that touted itself as the craft cannabis farmer’s friend—right up until the day founder Mowgli Holmes revealed his master plan.

Ready player one: Mowgli Holmes & Phylos Bioscience

In March 2019, Phylos Bioscience founder Mowgli Holmes stood before a crowd of high-net-worth investors in Miami and prepared to give a sales pitch. Billed as North America’s premier gathering of cannabis capitalists, the annual Benzinga Cannabis Capital Conference brings together entrepreneurs and investors who want to enter the booming industry.

Notably absent from the proceedings: cannabis growers, at least the kind who believe that farming shouldn’t require an eight-figure market cap.Phylos Bioscience offered cannabis growers a way to protect the strains they'd spent years breeding.

You know the ones I mean: the OG underground heads up in the hills who kept the plant alive through decades of prohibition and now hope to find a toehold in the legal industry.

When Mowgli Holmes founded Phylos in Portland, Oregon, in 2014, those salt-of-the-earth weed farmers were his target demographic. They’re a cagey, distrustful lot, but Holmes steadily won them over with a virtuous story. Phylos, he said, would use cutting-edge technology to safeguard the plant’s incredible genetic diversity, while protecting small-scale growers and breeders from patent trolls and predatory Big Ag corporations.

Above: Phylos founder Mowgli Holmes outlines his vision at the 2017 CannaTech conference.

Creating a ‘galaxy’ of strains

In 2015, Holmes explained his strategy to Cannabis Now:

“We keep hearing rumors—so and so lives way out in the Mendocino hills, he’s been growing this and that for 30 years without stopping, never hybridized it. And so we’ll send people out to track it down or try to get word to them. It’s not easy. People are a little nervous about this kind of thing, of course.”Holmes coaxed growers into having their heirloom genetics sequenced—and pay for the privilege.

Strain by strain, Holmes coaxed growers into having their unique heirloom genetics sequenced and added to a publicly accessible database—and pay for the privilege. Phylos’ online portal, dubbed the Galaxy, includes a 3D visualization tool that uses DNA data to map the relationships between thousands of cannabis varieties like constellations in the night sky.

Phylos: the boom years

Investors loved the Phylos story. They pumped more than $14 million into the company between 2014 and 2019.

Farmers and breeders also liked Phylos, and they loved Mowgli Holmes. The company founder’s personal style combined hippie values (he grew up on an Oregon commune) with scientific expertise (he earned a PhD from Columbia University). And his public statements left no doubt where his loyalties lay.

Phylos 2016: ‘We fucking hate Monsanto’

Here’s what Holmes told Vocative in 2016:

“We fucking hate Monsanto. If we can’t find a way to create a craft, artisanal industry, where lots of little people who really lavish love on interesting plants can be involved, and we just get this Anheuser-Busch industry, it’s going to suck.”

Some growers signed up simply because they liked the idea of participating in a scientifically significant exploration of the cannabis plant as a species and wanted to help Holmes fight back against Big Ag. Others joined to establish a “prior art” claim in case of future patent disputes.

Why establishing ‘prior art’ is important

Anyone applying for a patent from the USPTO must prove that their invention is new and non-obvious. The simplest way to reject or invalidate a patent claim is to show what’s known as “prior art”—evidence that the invention was already publicly known or available before the effective filing date of the patent application.

By registering their cannabis strains with Phylos, individual growers and breeders hoped to establish the prior art required to block any future patent claims on those same strains.

The USPTO uses this four-part test to evaluate patent applications. (Gillian Levine for Leafly)

Legal, illegal: patent office doesn’t care

But what about federal law? Cannabis is still a Schedule 1 narcotic according to the US government. So how can you effectively establish “prior art” when the invention in question is illegal?

I contacted the USPTO to find out. They sent the following reply via email:

“The evaluation of prior art for cannabis plant is the same as any other application under review. Extensive search of the prior art in multiple commercial databases are conducted to thoroughly search the claims as compared to what’s already been taught in the public domain. If the strains are already present in the public domain then the claims are evaluated based on the teachings of prior art.”

The USPTO statement also noted that patent applicants are “under duty of candor” to provide anything they know about potential competing claims, and there are also legal means by which members of the public can challenge the validity of an existing patent.

Phylos 2019: They fucking love Monsanto

At the Benzinga investor conference, Holmes at long last pivoted from hippie to capitalist. He opened with a shot at the small farmers who’d trusted him with their prized DNA:

“Compared to how it’s going to be in a few years, [cannabis] kinda sucks right now…”

“In a few years, all the cannabis that’s around right now will be replaced by new, optimized, specialized plants… Our company is developing this next generation of plants, and it’s not going to take very long either.”

Over the past century, Holmes said, “every other major crop has been through an incredibly complex process of plant improvement, for every major important trait.” Only prohibition has kept cannabis out of the Big Ag loop—and that’s about to change, and quickly, because advanced technologies and techniques have vastly sped up the process of breeding.

Then came his big finish.

Bringing Syngenta, DuPont veterans aboard

Holmes name-checked a few members of the Phylos Bioscience Advisory Board, noting that they all have equity in the company. Like Ron Wulfkuhle, who once headed the GMO corn division of agrochemical giant Syngenta. And Barbara Mazur, who recently retired from DuPont Pioneer (“the world’s leading developer and supplier of advanced plant genetics”), where she worked in acquisitions.

“Having these guys around is just critical for us because we’re building a company that’s ultimately going to be acquired by that universe,” Holmes said. “We need to make sure we’re building what they need us to be building.”

Happy 4/20, farmers

On April 16, 2019, about a month after Mowgli Holmes’ Benzinga presentation, and just four days before the annual cannabis holiday of 4/20, Phylos publicly announced that the company would soon begin an in-house cannabis breeding program.

To many of the old heads who offered genetics for inclusion in the Galaxy, this felt like a cold betrayal. Breeders had been sold on the idea that Phylos was building “the world’s largest database of hemp and cannabis genetics” in order to prevent Big Ag companies from pushing them around. Now Phylos was using that same data to compete against them.'So, you stole the genetics I paid you to test?'

Mz Jill, cannabis breeder, responding to the Phylos announcement

Mz Jill, one of the world’s best known cannabis breeders (she created Agent Orange and Jilly Bean, among others), expressed the outrage felt by a lot of her colleagues. “So, you stole the genetics I paid you to test?” she wrote in an Instagram post. “You told me this wasn’t true!”

No, no no, argued Holmes, including in a 9,000 word interview on the subject.

In an email to Leafly, he made his case more succinctly:

“We didn’t steal our customers’ plants, data, or IP. That data can’t be used for breeding plants, and, when customers gave us permission, we made the data publicly accessible. We’re also not planning to replace all the cannabis out there. We have always been supportive of the craft flower market, and when we do release varieties for that market, they will be open source and available for anyone to breed with. The large-scale market is a different story. Cannabis is not adapted to large-scale cultivation. It needs a lot of work, and it’s our job as a crop science company to develop varieties that really work for that market.”

Former Phylos employee speaks out

Despite these denials, many people reported feeling misled by Mowgli Holmes.

In a pseudonymous post published earlier this year in High Times, a disillusioned former Phylos employee described being bamboozled into pushing the company line when talking with growers. The ex-staffer claimed “the brass at the top of the company didn’t give a shit about the [cannabis] community.” The former employee wrote:'Phylos has chosen to support Big Ag over craft botanists. They took the money. They fucking blew it.'

Former Phylos staff member

“[Phylos] has chosen to support Big Ag over craft botanists… They had a real, solid chance with one of the most valuable crops on earth as it emerges into full marketplace acceptance to stand with the right people, and change the way the game of agronomics is played. Instead, they took the money. They fucking blew it.”

The Open Cannabis Project closes

Backlash started popping up on social media immediately after the company’s April 16 announcement. It spiked a few days later when somebody began circulating a YouTube video (since taken down) of Holmes speaking in Miami at the Benzinga conference. Soon after, the Open Cannabis Project (OCP) voted to disband itself.

Conceived and created by Phylos ostensibly as “a project to protect heirloom varieties from overbroad patents as cannabis transitions into a legal market,” the OCP issued a statement announcing its own self-immolation, which also included an apology for playing “a key part in shaping Phylos’ public image as altruistic and science-loving protectors of the cultivation community.”

The OCP had already splintered off from Phylos in 2017 to form an independent organization, but the board felt nothing would ever remove the stain from their work.

Next, the Cannabis Classic broke ties with Phylos. Oregon’s premiere cannabis competition and tasting event had previously offered winning entries a free listing in the company’s solar system of strains. Mowgli Holmes had been part of the event’s original thought leadership circle. But no more.

“The bottom line is transparency,” says Steph Barnhart, the Cannabis Classic’s longtime program director. “We took the opportunity to stand beside the farmers we work with, and also to update our own data privacy policies.”

Phylos pushes back

Meanwhile, the angry comments online just kept building. Phylos fired back on Instagram with a lengthy response that was at times evasive, contrite, self-aggrandizing and opaque:

“It’s been suggested that we’re claiming ownership over plant samples that have been sent to us and leveraging our genetic database to compete against our customers. That would be really f*cked up. But it’s not true… We have no claim to any of those plants. And as for bringing dead plant samples back to life, it’s just not possible. And if it was, we wouldn’t do it, because they’re not our plants.”

At first glance, a strong pushback.

Holmes used a variation on the word fuck (just like how he “fucking hates Monsanto”) and flatly denied the allegations. But we’re dealing with a master of double talk. So what exactly is Holmes denying, and more importantly, what is he not denying?

Industry pros not pleased

Seth Crawford is a leading cannabis breeder and co-founder of Oregon CBD, a federally legal cannabis research and development company and CBD-rich hemp seed supplier.

In September 2014, Crawford was serving on the Oregon Medical Marijuana Advisory Board, and also teaching at Oregon State University. After reading an article in The Oregonian that profiled Phylos, he got in touch and arranged for a tour of their lab.'Mowgli is a brilliant guy, but it was clear from the outset that he had a specific vision of what was to come, and that was Big Ag moving in.'

Seth Crawford, Oregon cannabis breeder

“Mowgli is a brilliant guy,” Crawford says, looking back five years later, “but it was very clear from the outset that he had a specific vision of what was to come, and that was Big Ag moving in and small farmers getting trampled. What set me back in our conversation was that he started playing devil’s advocate, and saying if these small farmers are going to get crushed anyway, why should we try to support them?”

Crawford says from that moment on he has advised people to be wary and not submit their strains to Phylos.

“I just assumed they were trying to scoop up as much data as possible and then get bought out by one of the Big Ag companies that do most of the world’s seed production.”

Next: A mysterious company called Bioscience Institute is patenting cannabis cultivars at an alarming rate. Who really owns the company’s patents?