How Legalization Changed Humboldt County Marijuana

In an isolated Northern California community, the last remnants of the counterculture are confronting the future of cannabis.

For more than forty years, the epicenter of cannabis farming in the United States was a region of northwestern California called the Emerald Triangle, at the intersection of Humboldt, Mendocino, and Trinity Counties. Of these, Humboldt County is the most famous. It was here, in hills surrounding a small town called Garberville, that hippies landed in the nineteen-sixties, after fleeing the squalor of Berkeley and Haight-Ashbury. They arrived in the aftermath of a timber bust, and clear-cut land was selling for as little as a few hundred dollars an acre. In their pursuit of self-sufficiency, the young idealists homesteaded, gardened naked, and planted seeds from the Mexican cannabis they had grown to love. They learned the practice known as sinsemilla, in which female cannabis plants are isolated from the pollen of their male counterparts, which causes the females to produce high levels of THC. The cultivators smuggled in strains of

Cannabis indica from South Asia and bred hybrids with sativas from Mexico. They learned to use light deprivation to encourage premature flowering, and they practiced selective breeding to isolate for the most desirable potency, scent, and appearance.

In the years that followed, the back-to-the-land movement, which began as a protest of American materialism, was increasingly subsidized, in Humboldt, by profits from cannabis. In the nineteen-eighties, as the war on drugs escalated, the growers responded by developing techniques to cultivate cannabis indoors or beneath trees. Their children, many of whom grew up poor, were less inclined to pursue “voluntary simplicity” for idealistic reasons. The cannabis industry represented the best living they could make in the place where they grew up, and a fairly lucrative one, especially after California legalized marijuana for medical use, in 1996. For those from the older generation who had believed that “dropping out” required serious economic sacrifice, the crop was the original sin of Humboldt’s Eden. Jentri Anders, the author of “

Beyond Counterculture,” an anthropological study of the back-to-the-landers of southern Humboldt County, wrote, in 2012, “I believe I realized much earlier than most that, if there was indeed a shared vision, it was in grave danger of being swamped, distorted and subsumed by the advent of the growing industry.” She continued, “I feared early on that the entire geographical area, mainstream and hippie alike, would come to be defined by the outside world through the lens of the marijuana industry, and that is exactly what happened.”

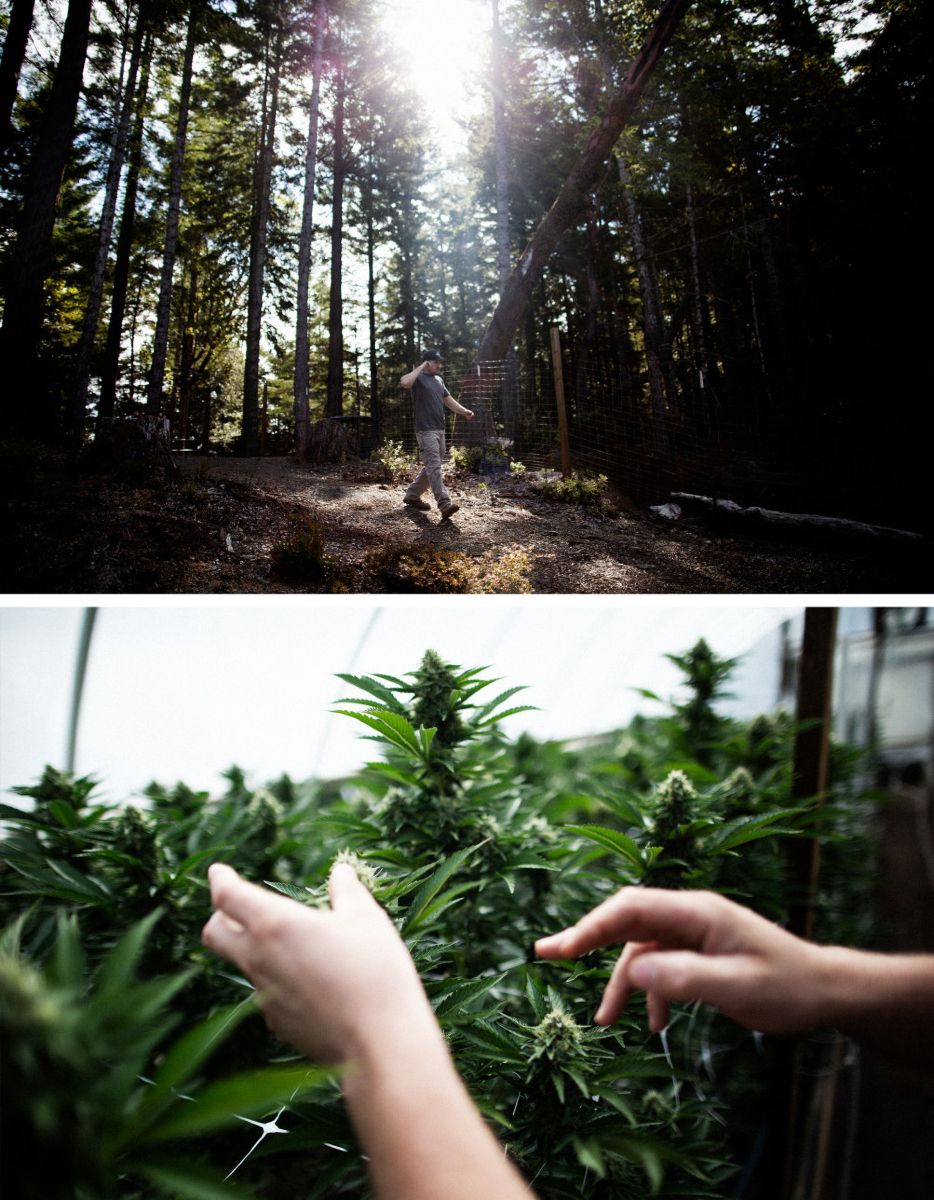

In 2016, operating under California’s medical-marijuana laws, Humboldt County officials began to try to license their half-hidden industry for the first time. Farmers who had been hiding from law enforcement for years were asked to present themselves to authorities and to comply with new commercial-growing ordinances. Statewide legalization of recreational marijuana for adult use followed two years later. Before legalization, people grew cannabis however they could and developed methods to avoid getting caught by law enforcement. Regulation demands a different set of skills. Instead of burning records, farmers must now practice accounting. Instead of loading their crop into duffel bags and sending it out of state, they have to learn branding and marketing. Legalization brings with it the costs of taxes, permitting, compliance, and new competitors. It has also occasioned a rapid drop in price. Now Humboldt County is experiencing not only an economic crisis but also an existential one. What happens to a group of people whose anti-government ethos was sustained by an illegal plant that is now the most regulated crop in California? Forced into the open, and facing the very real possibility of economic extinction, the farmers of Humboldt are now trying to convince regulators and buyers that these outlaws who had profited off prohibition were not greedy criminals but people who stood for something: stewardship of the land, the biodiversity of a crop, resistance to corporate consolidation, and a spiritual connection to a psychoactive plant.

Garberville, the supply hub of southern Humboldt County, is perched on the south fork of the Eel River. The town’s main street, Redwood Drive, can be walked in five minutes. Garberville has the rough edges of a gold-rush town, but with peace flags and hemp lattes. It’s a place where men in Carhartt jackets and hunting camo drink ginger Yogi tea and park muddied Dodge Rams outside the Woodrose Café, where they eat organic buckwheat pancakes. The town has a natural-food store where you can buy locally sourced Humboldt Fog cheese, and a home-goods store where you can buy a wool mattress or a composting toilet. When I visited in February, the marquee of a shuttered movie theatre in town bore the slogan of a newly formed visitors’ bureau: “Elevate the Magic.” But Garberville did not seem entirely ready to make itself over as a place for a romantic getaway—forty years of paranoia and chosen seclusion are not easily dispelled. The town relies on a cash-heavy, still partly clandestine economy, and it has a significant population of homeless people with drug dependencies. Locals advised me in advance to avoid certain motels. I checked into the local Best Western, where the receptionist told me that the rule she had learned when she moved to Garberville was never to go down a dirt road.

A farmer named Jason Gellman picked me up at the hotel on a night of pouring rain. He drove a gray Ford pickup truck—a four-door, high-clearance rig, which looked imposing on the outside, but, once I clambered up and settled in, it was like floating in a soundproofed cloud. Gellman is thirty-nine years old, clean-shaven, and tan from working outdoors. He wore a gray hooded sweatshirt, with green stars down the sleeves, and a flat-brimmed baseball hat, which bore the logo of his business, Ridgeline Farms. My ears popped as we drove, heading to Ridgeline on a road with no shoulder that ascended from town. We passed a rock barrier that had been spray-painted white and had the words “

STAY CLASSY SOUTH HUM” written on it, in green. We splashed through puddles, and the windshield wipers were on high. The torrent outside was Shakespearean, but Gellman was pleased with the weather, which was like the winters he remembered from his childhood—weather, as he put it, in which people either got pregnant or got divorced.

Gellman’s parents were hippies who moved to Humboldt County when he was two years old, in the early eighties. They eventually managed to buy their own property, in an enclave near Garberville called Harris. Gellman’s mom did beadwork, and his father did leatherwork and carpentry. They grew their own vegetables. And, like many of their neighbors, the family grew cannabis. At that time, ten pounds of marijuana—the amount produced by eight or ten plants in a harvest cycle—could be sold for as much as forty thousand dollars, enough to support a family that grew most of its own food.

“We grew up really poor,” Gellman said, as we arrived at an electronic gate at the entrance to his property. Gellman is a fisherman, and the gate was decorated with stainless-steel salmon. He rolled down his window and typed in a code, and we drove up the driveway to a large, beige house. Gellman laughed and said, “Here I am talking about how poor we were as we pull up to this.” It looked more like a house you would find in a gated community than one on a mountaintop hundreds of miles from a major city. A border collie and a wolfish mutt wandered out of the garage and stood in the rain to greet the pickup. We passed through an entryway into a spacious open-plan kitchen that looked onto a high-ceilinged great room with a fireplace.

In Humboldt County, cannabis is known simply as “the plant.” Gellman grew up with the plant, pruning its leaves for his parents as a child. He can’t remember exactly when the federal government first raided the family farm, only that he was six or seven years old, which would have been around 1987. He told me, “I was sitting on the porch and a giant military helicopter was like a hundred feet over our house, banking on our house, and my dad comes flying up in the four-wheeler, yelling, ‘Get in the rig!’ ” When they returned later, the cannabis had been cut down; their house was ransacked. Busts, which sometimes landed growers in jail, started happening more often after 1983, when the Reagan Administration began the Campaign Against Marijuana Planting, a paramilitary operation also known as

CAMP. Shortly after the first bust on the family property, Gellman’s parents split up. His dad continued to grow his crop in the same place every year. On years when the farm got busted, his dad would get depressed for weeks. Christmas would be cancelled.

Video From The New Yorker

Why Noise Pollution Is More Dangerous Than We Think

Most years, however, were good. Many of the children Gellman played with at school came from families who grew cannabis, although the subject was not openly discussed. “We couldn’t tell anyone, and that was just how our life was,” Gellman said. “You didn’t think it was bad, because when your dad does it and your mom does it, every single person, every single friend, grows weed—every one of their family members grows weed—it’s not looked upon as bad. It still isn’t bad, but you knew the outside world thought of it as bad.” Many of the children of cannabis farmers had a conflicted relationship to law enforcement. Another second-generation farmer, Wendy Kornberg, told me that one of her earliest memories was of a cop in a helicopter hovering over her house and giving her and her mom the middle finger. “That was the mentality,” she said. “ ‘You damn hippies need to go somewhere else and do something else.’ ”

Gellman grew up fishing, hunting, riding his bike, and playing in the woods. At harvesttime, there would be parties outside, under the moon. Families would grow “pencil patches,” as one farmer called them, sections of the crop whose proceeds would go to underfunded schools in the area. By selling their cannabis, the back-to-the-landers funded a community center, the Redwoods Rural Health Center, and KMUD, the nonprofit radio station on which the Civil Liberties Monitoring Project, an organization started by local farmers, broadcast the movements of law enforcement in the area. Residents started Reggae on the River, an annual music festival, which attracted thousands of people every summer. The crop helped fund local newspapers and growers supported the Humboldt chapter of Earth First!, which organized campaigns to preserve the area’s old-growth forests.

The community also faced the kinds of problems that are bound to occur in an isolated county where people kept their savings in cash, drugs were easily accessible, and nobody called the cops when things went wrong. Gellman lost friends to drunk driving on Humboldt County’s winding mountain roads. Two friends were murdered during pot deals gone bad. He lost friends to suicide, and later, as the heroin and meth problems that have affected rural areas around the country reached Humboldt, to drug overdoses. At the age of thirty-nine, he has a dozen laminated portraits in his home, memorials to friends who died. “There were a lot of deaths,” he said. “But I think it’s just because we know so many people. We have so many friends.”

Humboldt County’s first generation of cannabis growers used the crop as one of several sources of income. The second generation “worked hard, but it was different,” Gellman said. “It was more growing weed for money,” as a career. Gellman grew his first patch of cannabis at fourteen. In high school, he helped out on his dad’s construction crew, but growing the plant was more lucrative. He worked for other growers, spending winters in the woods monitoring clandestine greenhouses, and he eventually acquired two pieces of land: the farm I visited, where he lives with his wife and two sons, and a piece of property farther up in the mountains, in Harris.

In 1996, the state passed Proposition 215, which exempted patients and caregivers from criminal marijuana laws. The medical-marijuana movement, which had been building for years, was led by

AIDS activists, who wanted the right to use marijuana to treat symptoms of the disease. In Humboldt, the bill was received quietly—activism tended to attract the attention of law enforcement—but the growers soon adapted to the new legal paradigm, posting their medical marijuana cards on their fences as cover. California was slow to enact regulation under the medical-marijuana laws, and the farms in Humboldt operated in a legal gray area, monitored by a small, rural police force with little ability to control the trade. “People would get a number of 215 cards”—recommendations from a doctor to medicate with cannabis—“and then they would cultivate,” John Ford, Humboldt County’s director of planning and building, said. “It became difficult to tell who was legal and who was not.”

At first, because federal law still banned marijuana, most people feared the consequences of growing more than ninety-nine plants, the limit set by Proposition 215. But every year some farmers pushed their luck, planting bigger grows that were destined not for medical coöperatives in California but for the black market. Meanwhile, the medical-marijuana movement spread across the country, with more than a dozen states legalizing medical cannabis by the beginning of the Obama Administration. In 2009, the Attorney General, Eric Holder, announced that the federal government would not put resources toward prosecuting people who complied with their state marijuana laws.

All of this created the conditions for what’s now referred to in Humboldt County as the Green Rush. Newcomers arrived, from the East Coast, from Texas; there was an influx of immigrants from Bulgaria. Cannabis farmers started growing as much marijuana as they wanted. They diverted water from the rivers to irrigate their crops. They dumped pesticides into the watershed. They grew plants in national forests and state parks. They flattened mountaintops. The profits were high, and the risks were low—a grower who ran a big farm for two years could make out with two million dollars and then abandon the property, leaving the land a wreck. “The state had the onus to manage the medical system, and they refused to set up any kind of regulatory system, any kind of licensing system, any kind of ownership system,” Sheldon Norberg, the author of a memoir called “

Confessions of a Dope Dealer” and a member of the California Growers Association, said. At harvesttime, busloads of young people looking for seasonal work trimming buds would descend on Garberville, where they were vulnerable to exploitation.

In 2015, almost twenty years after the passage of Proposition 215, California passed the Medical Marijuana Regulation and Safety Act, in an attempt to better control the trade. The next year, under the terms of the new law, Humboldt County’s board of supervisors passed its first commercial-cannabis-growing land ordinance. Gellman was among the first to apply for a permit under the new system, despite controversy among his friends. Some farmers in Humboldt County saw the new regulations as a trap. They feared that attending an information session would mean turning themselves in. Gellman spoke of his own decision to go legal in the terms of the embittered end of a very long war. “I’ve had a great life,” he said. “I don’t want to go to jail. I’ve seen too many of my friends go to jail.”

Gellman thinks the county has used the permitting process as an excuse to correct the mistakes of a multigenerational libertarian experiment. The back-to-the-landers had not considered building codes when they constructed their homes and outhouses and catchment ponds and solar grids. “Basically, everything they’ve always wanted us to do—permit stuff, fix roads, get our wells all done right—they had us,” Gellman said. To comply with rules about water use, generator noise, fertilizer storage, and road maintenance, farmers had to hire consultants, lawyers, and engineers. To comply with environmental protections for spotted owls and marbled murrelets, they had to hire a bird-watcher “to come and sit at your house and look for a bird for four thousand dollars,” Gellman said. (The ordinance requires anyone applying for a permit to bring in a “qualified biologist” to conduct “a disturbance and habitat modification assessment” on the land, partly in response to pressure from local environmental groups.) The farmers complained that the county was sucking them dry and putting a significant percentage of the local economy at risk in the process. Ford said that old logging roads were never meant for daily use, and diverting water from streams to cannabis fields takes a toll on the surrounding ecosystems. He framed the conflict as, in part, a cultural one, between the government and a group of people that had always avoided it. “Those are the normal costs to anybody,” he said. “Whether you’re building a single-family home or beginning a business, or constructing a building, you would be expected to minimize and mitigate your impacts.”

And then, in the middle of this, Proposition 64 passed.

In the lead-up to the 2016 general election, Californians filed more than twenty ballot proposals to legalize marijuana. The one that made it to the November ballot was the Adult Use of Marijuana Act, or Proposition 64, whose success was due in part to its backers: Sean Parker, the founder of Napster and former president of Facebook, and George Soros, the billionaire philanthropist, were major donors, as were a committee funded by the dispensary-finding app Weedmaps, and a company that invests in the cannabis-news Web site Leafly. In the voters’ guide for the election, the campaign advertised “tough, common sense regulations,” so that marijuana would be “safe, controlled, and taxed.” Supporters of the measure projected tax revenues of a billion dollars.

Sixty per cent of the voters in southern Humboldt County resisted Proposition 64. Cannabis farmers told me that they opposed the legislation because it included high licensing fees and a fifteen-per-cent tax rate on cannabis purchases, which would discourage growers from leaving the black market and put those who did at a competitive disadvantage. It bothered them that three million dollars of the tax revenue would go to the California Highway Patrol, an old nemesis. But their primary worry was that the law did not do enough to protect legacy farmers from getting undercut by new agribusiness entrepreneurs. The new law was designed in a way that would allow cannabis to be grown as most crops are grown in the United States, as large-scale operations controlled by a handful of vertically integrated corporations. Proposition 64 created the conditions for “a land rush for wannabe drug-dealing venture capitalists,” Norberg told me. “And they are out there.”

Measures intended to protect small- and medium-scale farmers, such as a one-acre limit on cultivation for the first five years of legalization, were quickly undercut. In the aftermath of the law’s passage, the state announced a regulatory loophole that has allowed single entities to acquire as many small-scale licenses as they want. The law also mandated an industry of middlemen; cannabis farmers could no longer sell their own product directly to medical collectives or to retail outlets, and, instead, had to work with a licensed distribution company.

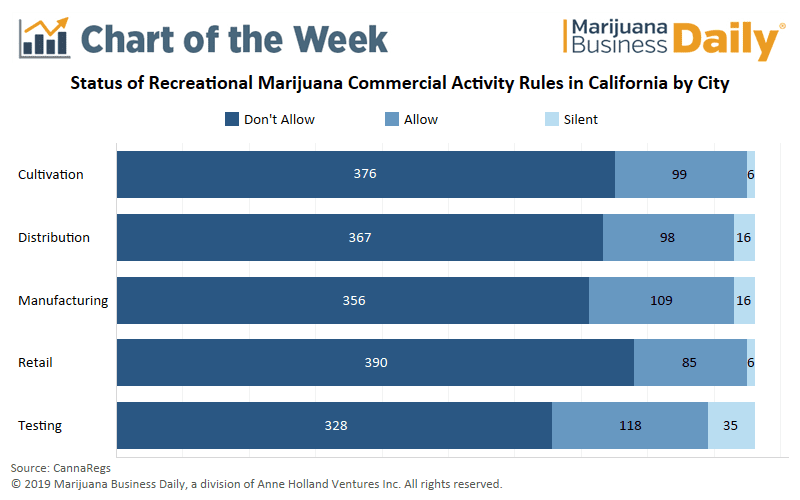

Several large agricultural companies began laying the groundwork to grow cannabis on an industrial scale in advance of statewide legalization. As of January, 2019, Santa Barbara County had received more cultivation licenses than Humboldt, most of them acquired in the dozens by large commercial farms. Prices started dropping, from more than two thousand dollars a pound, three years ago, to sixteen hundred dollars a pound, in 2017, to less than a thousand dollars a pound, last year. In Humboldt, farmers had spent their savings coming up to code, only to end up with licensed and legal weed that they could no longer off-load, now that the market was oversupplied.

In the wake of pot legalization, Humboldt farmers found themselves facing two options: they could try to operate in the legal market and risk bankruptcy because of the related costs, or they could remain in the black market, which was being pushed ever further underground. Humboldt County officials estimate that only a third of the county’s marijuana cultivators have attempted the permitting process. Local growers describe their neighbors who have chosen to avoid local and state permits as participating in the “unregulated,” “traditional,” or “free people’s” markets.

Gellman grows nine thousand six hundred square feet of cannabis on his farm. Some of the farms in central California are licensed to produce more than a million square feet, and their production costs per pound are lowered by mechanized farming methods and the scale at which they can produce.

The only way for a farmer like Gellman to survive on the legal market might be to succeed as a seller of top-shelf, premium cannabis—and, implausibly, he did just that. In 2018, he won the top award at the Emerald Cup, a trade fair for “licensed sun-grown cannabis.” Founded in 2003, as an illegal event, the Emerald Cup is now held at the Sonoma County fairgrounds, and tickets sell for as much as four hundred dollars apiece. Gellman’s winning strain, Green Lantern, was a high-THC, sativa-dominant hybrid with what a Leafly review described as a “peppery pine aroma.” From having trouble finding a distributor, Gellman went to getting requests from all over. So things worked out, at least for now. Gellman has a beautiful farm in his back yard. His family doesn’t have to fear that he will go to jail. The banner of Ridgeline Farms hangs in the high-school gym, honoring his donations to the local booster club. In March, the South Humboldt Chamber of Commerce named the farm its business of the year. It would be a happy ending, if so many of his friends weren’t still going under.

For several days this winter, I drove up and down the dirt roads of southern Humboldt, visiting cannabis farms. They were on hills and in hollows, but mostly on hills, because cannabis is a fickle plant that thrives in sunlight and gets moldy at low elevations. Some farms were on the grid and others were not. Some were ramshackle and homemade, with abandoned cars on their land or couches on their porches; others were sleek and pristine, and outfitted with granite countertops and stainless-steel appliances. The farmers had enormous, gentle mountain dogs—Newfoundlands, German shepherds, a Russian bear dog—who would greet me as I pulled into muddy driveways and snuffle at the ground, their fur wet with dew. One farm had a peacock named Henri, who stared out at the rain from beneath a porch. As I drove between farms, I listened to KMUD, the community radio station that residents started in 1987. The d.j.s played Moby’s “Porcelain” and a cover of Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit,” sung in Arabic.

At a farm called Emerald Organics Cooperative Inc., I talked with Jen Aspuria and Dan Kulchin in a geodesic dome they had recently built on a hillside. We gazed through a window at the tops of oak and madrone trees growing on the slope. Below us, in the forest, a small white “forest orb”—a mini dome—glowed in the gloom, like a satellite moon. Aspuria and Kulchin are planning to open a “bud and breakfast” in the domes, in the hope that hosting tourists might help carry them through the turmoil of legalization. The couple have secured a permit to grow ten thousand feet of cannabis on their ten-acre farm. Now that they are competing against farms that are many times the size of their property, their challenge has been finding a distributor. “We’ve had flowers that have literally rotted on the shelves and edibles that we’ve had to stop producing that we had demand for,” Kulchin said. Many of their neighbors have stopped farming. Some didn’t try for a permit at all, deciding, instead, to sell their land before real-estate prices fell. Others have gone to work for farms that are trying to scale up to compete, or have switched into forestry jobs, clearing brush.

“Essentially, the ability to sustain a loss is what the industry is right now,” Kulchin said.

“And how many more losses can you take?” Aspuria said.

As pretty as the domes were, their farm still had the mud puddles and equipment of a working operation. It was difficult to imagine Bay Area tech workers forgoing the gentrified pleasures of Big Sur or Sonoma or Mendocino to drive their Teslas to Garberville. I thought of a recent trip I had taken to San Luis Obispo, in central California, where some counties have been permitting pot farms the size of football fields. I had gone to a cocktail bar that had marble countertops and served a Martini flavored with lemon and myrcene cannabis terpenes. High-end city-stoner marketing was a lot about distancing marijuana from nugs and tie-dye, from reggae and the Dead. Most profiles of marijuana entrepreneurs that I’ve seen have featured white people dressed in business casual, not Phish fans with crystals and patches on their coats that read “U.S. Out of Humboldt County.”

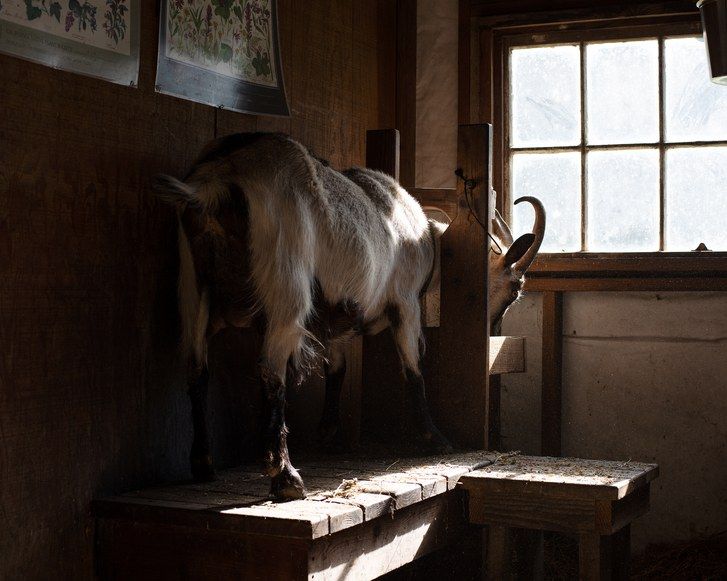

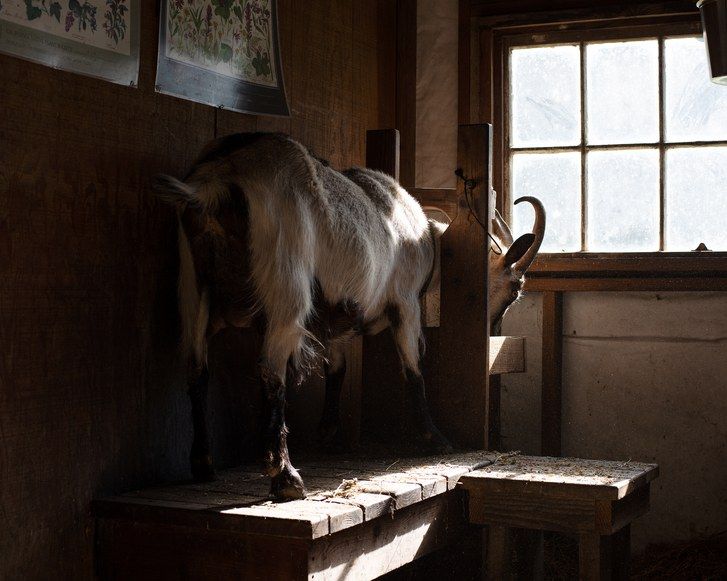

The farmers who survive will likely do so by making themselves part of the branding of their marijuana, styling themselves as representatives of an heirloom culture with a premium product—the cannabis version of the farmers pictured on cartons of organic milk. At Briceland Forest Farm, a couple named Daniel Stein and Taylor Thorton also grow vegetables and raise goats. They described their five-thousand-square-foot cannabis plot as just one crop on their regenerative agriculture farm. The most ambitious farmers speak not of cannabis strains but of “varietals,” of terroir and terpenes. One farmer, Tina Gordon, poured me glasses of Tang, Sunny Delight, and fresh-squeezed orange juice to make a point about the differences between marijuana grown indoors, in a greenhouse, and outdoors. Another farmer compared growing weed under a sunlamp to getting a fake tan.

Many of the farmers I met are placing their hopes in a distribution company called Flow Kana, which sources its product from two hundred farms in the Emerald Triangle, about sixty of which have contracts with the company. For companies like Flow Kana, the stories of the farmers are themselves a commodity. The symbolic value of the phosphorescent green of the moss-covered oaks, of the goats who fertilized the loam, of the ancient redwoods with all they have seen, is channelled to people in cities on the package of a pre-rolled joint. The C.E.O., a former produce distributor from Venezuela named Michael Steinmetz, told me that he based his business model on Sunkist, which handles the processing, distribution, and packaging of citrus fruits but does not grow a single orange. He framed the company as part of a new wave of “regenerative capitalism,” comparing it to Patagonia and Dr. Bronner’s. Flow Kana gives the contracted farmers a monthly guaranteed payment, and then processes the cannabis into products such as pre-rolled joints, extracts, and packaged flowers. The farmers then get a cut of sales, minus the company’s processing charges and other fees.

In Los Angeles, at a dispensary called Buds and Roses, I found Flow Kana’s jars of Gellman’s Green Lantern for sale, for forty-five dollars for an eighth of an ounce—ten or twenty dollars more than the cheapest California weed (although still less than the prices generated by prohibition in New York City, where the same amount of untaxed cannabis sells for fifty or sixty dollars). As prices dropped and the possibility of national legalization loomed, Steinmetz hoped that Humboldt’s small-scale cannabis culture could justify the price premium. Gellman was not the only person I spoke with who was simultaneously hopeful and skeptical. “It’s like beer,” he said. “Some people would rather buy a Coors Light than spend more money on a microbrew.”

When I spoke to second-generation farmers about the obstacles they face in bringing their farms up to code and surviving in the legalized market, they often spoke about their elders, alternating between reverence and younger people’s general gripe about the baby boomers—that the older generation’s idealism was enabled by cheap real estate and a strong economy, and that younger generations were burdened with the fallout. The Old Guard has fretted about the decline of the institutions they created, such as the community center and KMUD, without acknowledging the stress the next generation is under. “Most of the old folks that have been surviving off fifty pounds could not care less about creating a legal industry, so now the legacy they left us is ‘All right, here’s your massive land payment, and good luck!’ ” a farmer named Rio Anderson told me. “There’s not a lot of participation in creating a local framework for a legal pot industry.” He went on, “And here’s a huge set of super-judgmental liberal issues, like, ‘You guys are greedy, you guys are capitalists, you guys are ruining the environment, you guys aren’t participating in the community,’ you know?” So the second generation tries to live up to its elders’ expectations even as profit margins shrink. Anderson feels a loyalty to Garberville, where he runs a combined natural-food store and restaurant with his mother and sister.

Many of the older farmers are doing what they’ve always done—hiding from regulators—but others are calling it quits. Gellman’s parents are among those who no longer find cultivation to be worth the hassle. One night, I listened to a show on KMUD called “The Rights Organization,” hosted by a marijuana defense attorney named Eugene (ED) Denson. Denson was a creaky-voiced old-timer who had filed lawsuits challenging Humboldt County’s marijuana tax code. The focus of the evening was abatement letters, which had become the county’s primary method for cracking down on unlicensed cannabis farms in the era of legalization.

The Humboldt County Board of Supervisors started sending out the letters in 2017. It was not an investigative process. They looked at satellite images, and any white rectangles they saw were presumed to be grow houses. If the homeowner had not begun the process of applying for a cannabis license, the property received an abatement letter, threatening tens of thousands of dollars in fines. John Ford told me that the program was showing results—most growers who have received abatement letters have chosen not to continue cultivating marijuana.

“This is weird, but the county enforcement unit has done more to wipe out cannabis farms in a year than law enforcement did for twenty-five years,” Denson said, on the radio. “Way more. They have attacked seven hundred people. I mean, even

CAMP at its height was lucky to hit, say, fifty in a year.”

“I think it’s an excuse!” a caller named Emma Nation said.

“Well, it’s a revenue raiser, that’s for sure,” Denson said.

Cannabis was always a “value-based system,” Nation said. Growing the plant, she continued, was “a moral right, if not a legal right,” because it provided a way for people to “express themselves.”

A caller asked just how much marijuana he would still be allowed to grow under a medical license. The answer was a hundred square feet of canopy. “That’s nothing,” the caller grumbled. Another caller complained that the hosts were too focussed on the county regulations, rather than on the drop in prices. “The economy is bad here because it’s legal, and there’s big business getting into it, not just in Humboldt County—all over the world!” he cried in dismay. They discussed Governor

Gavin Newsom’s recent promise to send in the National Guard to eradicate illegal grows. Bonnie Blackberry, one of the founders of the Civil Liberties Monitoring Project, which tracked the actions of law enforcement in the nineteen-eighties, got on the phone and suggested that the project might need to be resurrected.

“I’m going to say something real quick, and everyone can chew on this for a bit,” Denson said. “Southern Humboldt pot growing started off as a libertarian experiment: back-to-the-landers in way-back-at-the-end-of-the-road seclusion, the government basically never showing up, they could do whatever they wanted. They were growing illegally so they could keep all the money, and that’s where the prosperity came from. Then they were unable to deal with the problem of evil. They could not enforce penalties, against, say, people who took all the water out of the creek, or something like that. Then, also, the thing grew out of hand. Suddenly, the endless supply of resources dried up, and action had to be taken.”

For multiple generations, the people of Humboldt thought that they had found a back door out of the mainstream economy. While small towns and family farms across America saw economic decline, Garberville held on to its main street, its independent businesses, and its reputation as a haven for people who did not fit in. Cannabis allowed the community to sustain the illusion that it was a place apart, but the conceit is now ending. You could blame the correction that has been playing out on the first generation, for naïveté; or on the second generation, for pursuit of profit; or on the county, for demanding changes; or on the state government, for not protecting small farmers. But Humboldt can no longer claim its independence, and it will now have to see if it can hold on to its values.

In 2017, when statewide legalization was on the horizon, a hundred and forty people gathered at the Mateel Community Center, in the town of Redway, to attempt to define the values of Southern Humboldt. The Mateel, like other local nonprofit organizations, was having trouble paying its bills, but the people of Southern Humboldt still gathered there for weddings and concerts and civic happenings. During a three-day conference, they expressed what was important to them, and then mapped and clustered and redefined these values until they were distilled into eight essential tenets. These included “We treat everyone with respect and compassion and empathy regardless of their capabilities, acknowledging that everyone is born with a pure spirit”; “We respect and value the beauty of our ecosystems”; and “It’s imperative that we in a positive way accommodate the continuing evolution of the counterculture, so that refugees are integrated in a way that respects human rights and existing communities while cultivating wellness, personal growth, generosity, accountability, and honesty.”