Europeans Once Drank Distilled Human Skulls as Medicine

“Corpse medicine” created a booming market for craniums, especially mossy ones.

BY

DIANA HUBBELLOCTOBER 22, 2021

Europeans Once Drank Distilled Human Skulls as Medicine

The gruesome concoctions definitely caused more harm than good. GETTY IMAGES

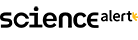

KING CHARLES II WAS ON his deathbed. The year was 1685, and the monarch had suffered a stroke. Doctors tried everything to save him, but the king was convinced that one particular remedy would work. Years before, Charles II had paid Oliver Cromwell’s own doctor and chemist, Jonathan Goddard, a handsome sum for the secret formula for Goddard’s Drops. The chemist claimed that his invention, which later came to be known as King’s Drops, was a kind of miracle cure for all manner of ailments. The recipe for this liquid concoction was complex, involving numerous components and multiple distillations, but its efficacy supposedly hinged on one crucial ingredient: a powder consisting of

five pounds of crushed human skulls.

Not just any skulls would do. According to medical wisdom of the time, the bones of an elderly person might contain some of the very illness the King’s Drops were meant to cure. “Ideally, [the skull] would be from someone who died a violent death at a young, healthy age,” says Lydia Kang, co-author of

Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything. “You wanted somebody who died in the prime of their life, so execution and war were ideal ways to get these products.”

By the end of his life, doctors were pouring 40 drops of this gruesome elixir down the king’s throat daily. Needless to say, the potion didn’t have its desired effect. King’s Drops and other bogus medical treatments may have sped up his demise on February 6, 1685. Yet the fact that the drops failed to save Charles II didn’t deter many other English people from making and drinking the concoction. In 1686, an Englishwoman named Anne Dormer wrote to her sister about the positive impact a little bit of skull juice had on her mental health. “I take the king’s drops and drink chocolate,” she wrote, “and when my soul is sad to death I run and play with the children.”

As he died, Charles II tried to stave off the inevitable with King’s Drops. GETTY IMAGES

The idea of ingesting human skulls from the freshly killed seems repulsive today, but it was shockingly common among British and other European aristocrats from the 16th century all the way up into the so-called Age of Enlightenment in the 18th century. Medical science was still very much an evolving field, one which left plenty of room for treatments ranging from the bizarre to the downright disturbing.

King’s Drops were especially popular, but medical books across Europe published all sorts of other recipes for various skull-related cures. Oswald Croll, a German alchemist, published a recipe for an epileptic cure in 1643 that called for three skulls from

men killed by violent means. In 1651’s

The Art of Distillation, English physician John French wrote up the following recipe for

“Essence of Man’s Brains,” which he touted as a cure for epilepsy:

“Take the brains of a young man that has died a violent death, together with the membranes, arteries, and veins, nerves … and bruise these in a stone mortar until they become a kind of pap. Then put as much of the spirit of wine as will cover it … [then] digest it half a year in horse dung.”

This jar once held human skull residue for medical use.

EINSAMER SCHÜTZE/CC BY-SA 3.0

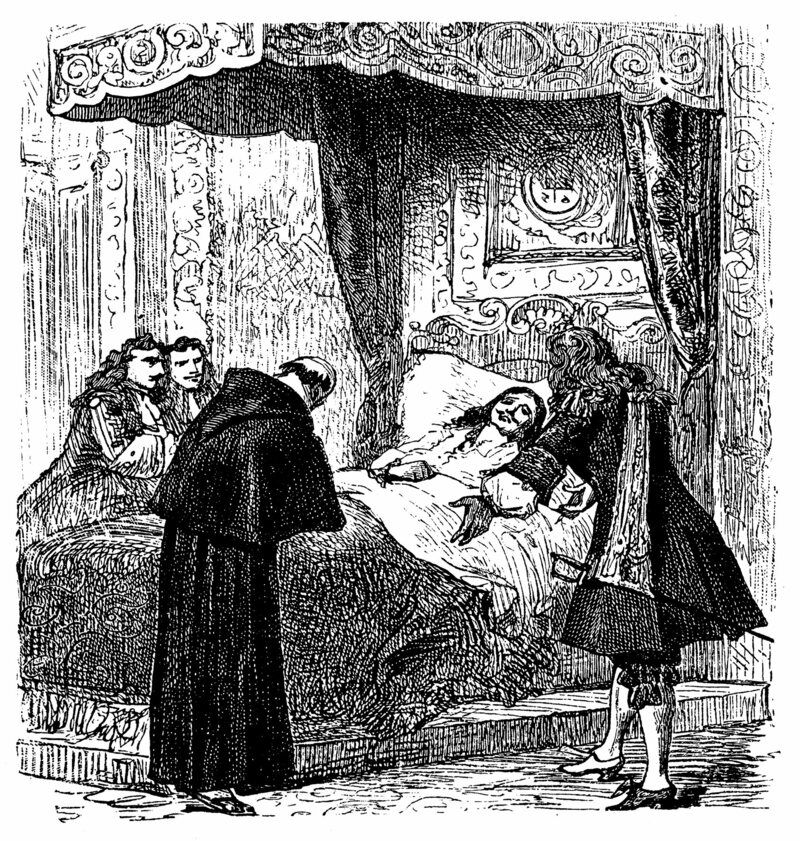

Much of this macabre fixation on corpse medicine had a single source. Theophrastus von Hohenheim, better known as Paracelsus, was a 16th-century Swiss alchemist, physician, philosopher, and all-around polymath. Prior to his work, the amalgamation of ancient Greek and Roman beliefs known as Galenism dominated European medical circles. According to Galenism, the body consists of different humors—blood, phlegm, and black and yellow bile—and the key to health was keeping them all in balance.

While Galenism led to some utterly ineffective medical treatments, it was nothing compared to the horror that came out of Paracelsus’s work. Essentially, his philosophy was that “like cures like,” or similar elements from outside the body could restore health within it. His book

Der grossen Wundartzney (Great Surgery Book) was one of the most influential medical books of its time.

According to Paracelsus, if someone’s illness centered on their head, the best remedy was to, in turn, consume part of the head of a healthy individual. Paracelsus advocated drinking the blood, powdered skulls, and other parts of corpses, particularly those of men in their prime who died a sudden, violent death, since their

“vital spirit” was so strong.

Paracelsus changed medical science in Europe with his writings.

WELLCOME COLLECTION/CC BY 4.0

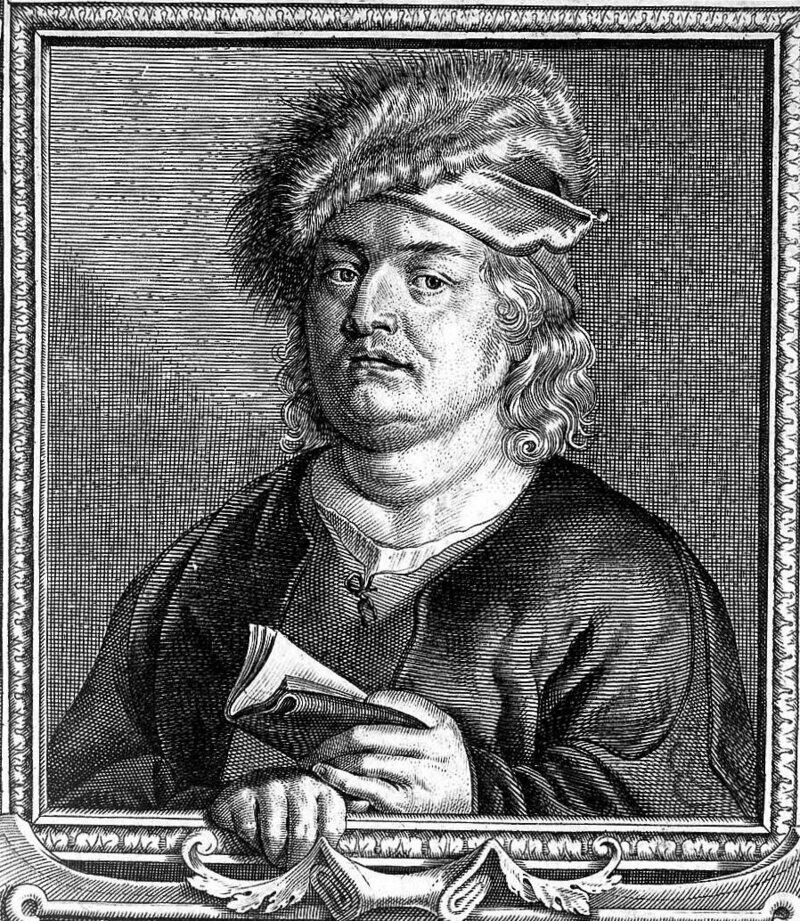

People eating human body parts to cure themselves became such a widely accepted concept that it crossed the Atlantic to New England, where the 17th-century Puritan town physician Edward Taylor enthusiastically touted all sorts of cannibalistic remedies in his handwritten

Dispensary. Taylor had an extensive list of useful human body parts, including “Man’s Skull” (“good for head diseases and the falling sickness,” or epilepsy) and “Moss in the skull of dead man exposed to the aire,” to stop bleeding.

While most of these cures did more harm than good, patients swore by them. Skulls and other body parts were mixed with chocolate, wine, hard spirits, or other substances that, when combined with a pinch of willful denial, may have made the afflicted feel better. “As with a lot of old-fashioned remedies, they were often mixed with other intoxicants like opiates or alcohol,” says Kang. “There was a lot of magical belief and placebo going into these.”

An ugly side effect of the Western obsession with corpse medicine was the demand it created for human remains. “In England, there was a huge trade in skulls and cannibalistic treatments,” Kang says. Executioner’s blocks were a popular place to procure the requisite body parts. A thriving, well-documented trade in

Egyptian mummies went on in Europe for years.

In this painting of botanist John Tradescant, the moss-covered skull is meant to evoke its medicinal usage.

PUBLIC DOMAIN

Whenever there’s a market for a particular commodity, no matter how unsavory, history dictates that some unscrupulous entrepreneur will find a way to fill it. “Often, they would go to Ireland because there were so many people who had died on the battlefield and there were so many skulls lying around,” Kang says. The English philosopher Francis Bacon once remarked that skull moss, which was thought to be good for nosebleeds, could be harvested from the

“heaps of slain bodies lying unburied over in Ireland.” Moss-covered skulls looted from the battlefields became a common sight in London druggist shops.

The marketing of their skulls for consumption was one more brutality in a long list of oppressions against the Irish at this time. The fact that there was money to be made, particularly from the export of skulls, seemed to be enough to keep anyone, English or otherwise, from questioning the ethics of this business for an uncomfortably long time. “Germany had a particularly big hunger for corpse medications,” Kang says. “So there was a brisk trade in pillaging Irish skulls and selling them to Germany.”

While there are documented records of skull sales as late as 1778, medical cannibalism in England trailed off in the 19th century. “You really start to see the physician’s understanding of anatomy [and] physiology come into more modern clarity,” Kang says, “when lot of these more magical theories start to disintegrate. They just don’t hold up against science.”

?

?

.

.