It is a gold rush moment, infused with a giddy end-of-Prohibition fervor. And if, given the high stakes, the desire for market dominance is understandable, the financial muscle and savvy of the big players have so far effectively shredded state lawmakers’ vision of a recreational pot business that would create opportunities for ordinary people.

IMO, and based my observation of legalization rollouts so far, this is because state governments are populated by idiots, both politicians and bureaucrats. This same "management contract" BS is going on in MD, and our commission also was completely and utterly CLUELESS.

It would be funny if it wasn't so sad.

By the by, this is a really good investigative journalism article. Spotlight group in the Boston Globe arose out of the Catholic clergy molestation investigation and reporting by the Globe (great movie, by the by, "Spotlight".

There will be more from this group on this subject.

You can’t own more than three pot shops, but these companies are testing the limit — and bragging about it

By Beth Healy, Dan Adams, Nicole Dungca, Andrew Ryan, Todd Wallack and editor Patricia Wen of the Spotlight Team. This story was written by Healy.March 21, 2019

Robert Leidy, scion of a wealthy Palm Beach family, struck a serious pose that night before officials in the small town of Athol.

In a dark suit and tie, he fixed his gaze on a careful script. There was no mention of the deep-pocketed investors backing him or the fishing yacht his company, Sea Hunter Therapeutics, was named after. Leidy talked about his lofty mission: to help a nonprofit business grow marijuana in an old tool mill there, and sell the product at its stores to people suffering from illness.

“Our passion is to enhance the quality of life for so many living in pain,” Leidy said.

But in his focus on the healing qualities of marijuana, Leidy offered little about the company’s actual, larger ambition. Despite the high-minded speech that October night in 2017, Sea Hunter had largely taken over operations of the nonprofit, Herbology Group, as part of a much broader strategy to capitalize on the state’s new recreational pot market and become a dominant player in Massachusetts and beyond.

In a state where no firm is legally permitted to own — or control — more than three stores that sell recreational pot, Sea Hunter is poised to test that limit. It has boasted to investors that it operates or has significant power over a dozen or more marijuana retail licenses. But you won’t see the name “Sea Hunter” on the shops; instead, they will carry names like Herbology, Verdant, and Ermont.

The only company that Sea Hunter Therapeutics acknowledges owning is Commonwealth Alternative Care, which has a store in Taunton (above) and plans to open stores in Cambridge’s Inman Square and Brockton.

Barry Chin/Globe Staff

Sea Hunter, along with a large rival called Acreage Holdings, is using complex corporate structures to acquire or manage store licenses from the Berkshires to Cape Cod, commanding high-interest loans and strict management contracts as they become quiet titans of Massachusetts marijuana.

Their aggressive growth plans are not just pushing the limits built into the state law, but may be busting them entirely. Their early moves also threaten the state’s promise to not just legalize recreational marijuana but to make the marketplace for the drug a fair one in which diversity of ownership is prized and small players have a chance.

Massachusetts, in short, had hoped to get legalization right. But out of the gate, that dream faces an existential threat, the Spotlight Team has found.

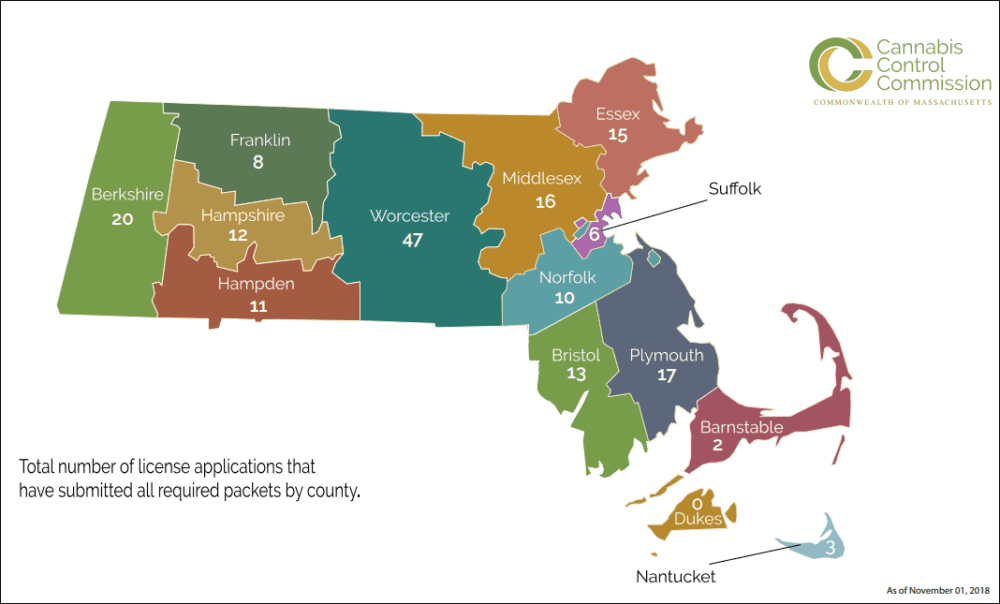

Of the 12 recreational shops that have opened so far here, all but two are owned by or have ties to large, out-of-state investors or multistate operators. Meanwhile, out of more than 120 applicants approved for a state program aimed at helping startups from minority and disadvantaged communities, not one has opened yet, largely due to a lack of funding.

The chairman of the state board in charge of regulating the marijuana industry says he’s not aware of any license-limit violations at this time.

“You can’t control more than three licenses, whether it’s direct or indirect, through subsidiaries or holding companies or shadow companies,” said Steven Hoffman in an interview at the Cannabis Control Commission offices this week.

Hoffman, a former partner at Bain & Co., said he also wasn’t aware of companies openly bragging to investors about controlling up to four times the number of licenses legally allowed here.

“If somebody says they’re controlling 12 licenses in Massachusetts, that’s really a stupid thing to say in a public document,” he said, “because they’re not going to be able to go forward.”

Both Sea Hunter and Acreage downplay with state and local officials their expansion plans here, insisting that companies in their network are independent operators and not under their control in the meaning of the law.

While Sea Hunter and its affiliated companies continue to pursue licenses in Massachusetts, Alexander Coleman, chief executive of the Cambridge-based firm, told the Globe that Sea Hunter is moving to become more of a technology and service provider in the cannabis industry than a national retail giant.

Acreage’s chief executive, Kevin Murphy, declined a request for an interview through a spokesman. The company’s president, George Allen, last year told the Globe that the company stays within Massachusetts law in its relationship with affiliated companies. “We don’t have a controlling relationship,” he said.

It’s hard to blame investors for seeing a big opportunity in pot. Since recreational marijuana became lawful here, two more states have jumped on the bandwagon, making 10 in all, and there is talk of federal legalization, as early as this year. Sea Hunter and other large companies are positioning themselves to take advantage of this booming new market, projected to generate $80 billion in annual revenue nationally by 2030.

It is a gold rush moment, infused with a giddy end-of-Prohibition fervor. And if, given the high stakes, the desire for market dominance is understandable, the financial muscle and savvy of the big players have so far effectively shredded state lawmakers’ vision of a recreational pot business that would create opportunities for ordinary people.

“When the big boys come in, it’s hard to compete. Now it’s big money, that’s the way it works,’’ said Alexander Eriksen, a former Massachusetts businessman who founded Verdant Medical Inc., a startup cannabis company, in 2016.

Cannabis Control Commission Chairman Steven Hoffman and Commissioner Shaleen Title at a public meeting on draft regulations for the pot industry.

Josh Reynolds for The Boston Globe

He said he was growing lettuce for $10 a pound in Millis, but realized marijuana could fetch $4,000 a pound. He wanted in, and became convinced of the medical benefits for some: “It can do amazing things for people.” So he poured $650,000 and two years of work into the venture before deciding he couldn’t afford to wait out all the state and city red tape. “I gave it up to Sea Hunter,” he said, to get out of debt and move on.

“You have to spend $1 million just to get an approval” from regulators, he said. “It’s very hard for regular people.”

It’s all happening so fast that small operators could scarcely get a toehold in the business before the big money arrived.

That’s true even in a state that had sought to put fairness — including social and racial equity — at the center of its cannabis rollout. Massachusetts lawmakers limited the number of licenses any single company could control. And they were first in the nation to include in the law a head start for small and minority applicants who wanted to become business owners, mindful that so many black and Latino people once faced criminal charges over minor marijuana infractions when the drug was illegal.

The National Cannabis Industry Association Seed to Sale convention was held last month at the Hynes Convention Center in Boston.

John Tlumacki/Globe Staff

But state policy makers failed to foresee just how hard it would be to control giant investors, often aided by well-paid lobbyists and lawyers, in a field that now has its own Marijuana Index to track the biggest cannabis companies in North America.

The marijuana industry naturally favors deep-pocketed players because traditional loans are almost impossible to get. The drug remains illegal at the federal level, so most banks don’t want to take the risk of lending to pot companies. As a result, some small entrepreneurs are being drawn into the arms of giants, with terms that some say are predatory and make it hard to succeed. Some are effectively signing away much of their autonomy to run their startups, with little to no oversight by state regulators at the Cannabis Control Commission.

State Senator Patricia Jehlen, a Somerville Democrat who was part of the state’s Joint Committee on Marijuana Policy, said the goal in setting license limits was to avoid a big-tobacco scenario, with a few giant brands dominating the scene. “The law was intended to create a system where Massachusetts residents could benefit from the new industry,” as owners, she said.

The battle for dominance in the state is a microcosm of what’s happening across the country, with national marijuana companies challenging rules in order to grab market share.

Several firms, for instance, have publicly claimed they have multiple stores in Maryland, where companies are only legally allowed to own one. iAnthus says it operates three stores it doesn’t own through management agreements.

The city of Los Angeles also bars entities from owning more than three licenses. Yet MedMen Enterprises operates five stores there under its brand. The company says two of those stores are owned by an investment fund, also based at MedMen’s headquarters.

“We play by the rules,” MedMen chief executive Adam Bierman said in an interview. But in New York, where MedMen has already maxed out at four stores, his company’s pending acquisition of PharmaCann would double that number to eight, testing the regulations. Officials are reviewing the deal.

“It’s a first,” Bierman said. “So the regulator has to figure out how they want to deal with this and they’ll set a precedent for going forward.”

RELATED: Beyond Massachusetts, states struggle to limit marijuana behemoths

Testing the legal bounds

In Massachusetts, a company can own or control a maximum of three stores that sell both recreational and medical marijuana. (Alternatively, firms can have three stores of each type, though few, if any, intend to sell only to the medical market.) Regulators define control as, among other things, the ability to veto significant events in a business operation.

Sea Hunter and Acreage both deny that they are bending or breaking the rules. But their security filings and investor pitches, reviewed by the Globe, raise legal questions.

Sea Hunter raised $250 million from investors last year and went public on a Canadian stock exchange, creating a Vancouver parent company called TILT Holdings Inc. Its founders, including Leidy and Coleman, are linked by blood or marriage to the Lilly Pulitzer family of fashion and publishing fortunes.

Acreage, of New York, claims to be the largest cannabis purveyor in the nation, and drew national media attention when it appointed as directors former Massachusetts governor and potential presidential candidate William F. Weld and John Boehner, a former House speaker.

Both companies are run by private equity and investment veterans; both have publicly traded stocks, with hundreds of millions of dollars at their fingertips. And both have offered investor pitches that seem to look right past Massachusetts license limits.

Sea Hunter and Acreage are trying to multiply the “rule of three” out over a much larger network. They have been buying or backing a series of businesses that each, in turn, is seeking to control up to three licenses.

Sea Hunter and its affiliated companies have just two stores open so far, a medical dispensary in Quincy and one in Taunton, along with pot-growing facilities at each. But it is shepherding at least 11 more retail locations through the licensing pipeline, under five different company names.

Marijuana plants in a grow room in Quincy operated by Ermont, one of a handful of companies with financial ties to Sea Hunter Therapeutics.

Adam Glanzman/New York Times/File

Among those are Verdant Medical, now being run by former Boston city councilor and onetime mayoral candidate Tito Jackson, with Sea Hunter appointees on the board. Another is the Herbology Group, the company that Sea Hunter pitched in Athol, a site the company ultimately abandoned in favor of other opportunities.

This approach to growing market share appears to violate the spirit of the law, according to rivals frustrated to be hemmed in by rules while some outliers seem to plow through them.

Some state officials want enforcement of this law to be a priority.

“In order for all the small businesses to have a chance, the opposite side of that coin is, no one can dominate it,” said Shaleen Title, another member of the Cannabis Control Commission. “No one needs to dominate it.”

To pot entrepreneurs considering joining Sea Hunter’s network, the company typically offers loans of at least $1 million, at interest rates of 14 percent or more, according to interviews and contracts reviewed by the Globe. The outlets usually rent their real estate from Sea Hunter and are often required to buy as much as 85 percent of their product from them as well. Some are required to pay out 70 percent of their cash flow until their loans are paid off. And if they want to sell their startups, Sea Hunter retains a right of first refusal.

Former Boston City Councilor Tito Jackson now heads Verdant Medical, a part of Sea Hunter’s network that hopes to open stores in Provincetown, Rowley, and Mattapan.

Nathan Klima for The Boston Globe

“These terms are extremely onerous in my opinion,’’ said Todd Dagres, a veteran venture capitalist in Boston and founder of Spark Capital, which so far is not in the marijuana business. “They are reflective of a lopsided financial relationship in which the founder has no leverage.”

With control of the loan, the lease, and the product sourcing, Dagres said, “I would worry about the lender in situations like this being the real owner, and the supposed owner being more of a front person.”

Coleman, 52, the head of Sea Hunter, denies this. He said owners are getting fair terms and have the freedom to negotiate how much product they buy from his company. He also denies that the loan agreements, and relationships with far more than three marijuana locations, amount to his company controlling more entities than are allowed under state law.

“That’s not our business model,” Coleman said.

He said Sea Hunter owns only one company outright, Commonwealth Alternative Care in Cambridge, and the three licenses under that umbrella, located in Cambridge, Taunton, and Brockton. The heads of other companies affiliated with Sea Hunter also each asserted to the Globe they will be sole “owners” of their firms, Verdant, Ermont, and Herbology.

But financial documents, e-mails, and interviews with people familiar with Sea Hunter’s operations show the company has significant financial and managerial control over its affiliates.

The company said as much in a November stock filing with Canadian securities regulators. Sea Hunter’s parent, TILT, in the disclosure said it had “the power to direct activities” at the Massachusetts marijuana companies.

Chief executives and chief financial officers of public companies in Canada — and the United States — are required to sign off on such financial filings.

But Coleman told the Globe that the document is inaccurate.

“I don’t know who was involved, it predates our CFO,” Coleman said. “The way they came to this is deathly wrong.” He acknowledged that as chief executive it’s his responsibility to review the filings.

He likewise sought to distance Sea Hunter from its claims to investors about millions of dollars in acquisitions and its control of marijuana companies, attributing them to a memo he said was sloppily written in the rush to grow the business.

“I mean look, struggling to raise capital, you really don’t spend a lot of time on the nuances,” he said.

“ The race to be the Coca-Cola of cannabis is just beginning. ”

— Kevin Murphy

CEO of Acreage Holdings

Coleman said the company is focused today on providing technology services to more than 1,000 marijuana locations across the country and laying the groundwork to become wholesalers of pot.

Acreage Holdings uses some of the same tactics as Sea Hunter, but appears to be pursuing a larger retail profile.

Acreage’s chief executive, Kevin Murphy, 58, who is from Madison, Conn., and attended the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, has said he believes “deeply in the potential for cannabis to heal and change the world.” In January, he landed an interview on CNBC at Davos, the big World Economic Forum where the financial and political elite mingle. And in March, he appeared with Boehner at South by Southwest, the Austin music mega-festival, arguing that Congress should make recreational marijuana use legal nationally.

Acreage’s chief executive Kevin Murphy (left) and former US House speaker John Boehner shared a stage during the 2019 SXSW Conference and Festivals in Austin this month.

Nicola Gell/Getty Images for SXSW

The company touts a presence in 19 states, and two dozen stores. Its strategy of expansion in Massachusetts seems to follow a similar playbook to Sea Hunter’s. Acreage admits direct ownership of just three stores, under the brand The Botanist, and says its relationship to nine others is through management contracts and loans.

Murphy gave only a written statement through a spokesman in response to the Globe’s request to interview him on licensing issues in Massachusetts.

“We are privileged to serve the citizens of Massachusetts, enabling access to safe, affordable cannabis to those who want or need it and in accordance with the state’s regulations,” it read.

Beyond The Botanist, the Globe learned of three other entities in Acreage’s network. One is Mass Medi-Spa, whose pitched battle to win a license on Nantucket shows how money is being thrown around in this arena.

In hours of hearings before the island’s town officials, representatives described Mass Medi-Spa as an independent nonprofit, with local board members and an arms-length relationship to Acreage. Documents reviewed by the Globe show a loan of up to $8 million from an Acreage subsidiary to the company, at a 15 percent interest rate, and involvement in virtually every aspect of the dispensary’s operation, from construction and hiring to public relations.

On the other side of the Nantucket license contest was ACK Natural, led in part by Boston hedge fund manager Douglas Leighton. The group has touted its dedication to Nantucket nonprofits, culture, and natural beauty. Both groups have spent months vying to be seen as the more local operator.

It is a battle that could have been over before it started. In December, just before the public showdown began, Leighton and Acreage’s Murphy had an intriguing private e-mail correspondence, copies of which were obtained by the Globe.

“Hi Kevin — While Nantucket may not be a big deal to you, it is to us,” Leighton wrote. He said ACK was in a strong position to win the license. But for $15 million, “We are willing to sell to you and move out of the way.”

Acreage didn’t bite, so the fight continued. But this week, Nantucket officials awarded the license to ACK Natural; it is unclear if Acreage will appeal.

In an earnings call with analysts earlier in March, Murphy declared, “The race to be the Coca-Cola of cannabis is just beginning.”

How the big firms rolled through

The early days of legal marijuana look quaint by comparison to the competitive ferocity of today. Just seven years ago, activists pushed through a ballot initiative to allow the medical use of cannabis. In those days, activists and regulators alike were careful not to raise alarms that they were promoting recreational use of marijuana, still seen by some as a gateway drug.

The ballot question, and the Department of Public Health regulations that followed, were crafted to appeal in a region known for its health care offerings. Nearly everyone could summon a story of a friend or loved one who’d suffered from cancer or other ailments that might have been eased by cannabis.

“The idea was, write it so that it’s appealing,” said Jack Corrigan, a lawyer and former Dukakis administration staffer who helped write the 2012 ballot question. “It evokes a sympathy for the patients,” he said.

To further smooth the path for pot, these new medical marijuana businesses were structured as nonprofits under state law. This was a way to mollify federal prosecutors, making them less likely to go after medical marijuana sellers, Corrigan said. It was also a way to make the legal sale of drugs more palatable to voters and lawmakers.

One of a number of marijuana products offered at a Taunton location by Commonwealth Alternative Care, which also hopes to open stores in Cambridge and Brockton.

Barry Chin/Globe Staff

But the nonprofit model turned out to be deeply flawed when it came to marijuana.

For one thing, it cost millions to get medical dispensaries going, and the nature of the product made it hard to raise money from conventional sources. Applicants had to show they had $500,000 available just to file initial papers. So cannabis entrepreneurs had to mortgage their homes and raise money from friends, family, and other nonbank lenders, often at interest rates as high as 18 percent.

And there was a mistaken notion in the rule-writing that no one would seek to earn profits from these companies. Officers and directors were not supposed to benefit from them. Who was going to take such a big risk with so little chance for gain?

So companies immediately looked for ways around the rules, creating for-profit entities linked to the nonprofits — an approach that Sea Hunter and Acreage have continued to use in some cases.

Jack Hudson launched Ermont of Quincy in 2013 by cobbling together loans from 20 different lenders, at rates of up to 18 percent, plus a significant amount of his own cash. Eventually, the debt burden became too great. Hudson turned to Sea Hunter, which paid $15 million to repay the company’s lenders and has taken on management duties, according to two people with direct knowledge of the deal.

Hudson blamed the early nonprofit design in Massachusetts for pushing out local operators.

“When I was looking for lenders, because no one could buy a piece of a nonprofit, you ended up with high-interest loans,” he said. “For some of us, it was incredibly difficult.”

State regulators stopped requiring the problematic nonprofit structure in 2017. But Sea Hunter and Acreage have continued to use that status for some associated companies, enjoying the public-relations advantages of nonprofits. The structure also has helped obscure their financial grip on the firms.

“We never bought Ermont,” Coleman said, phrasing his response carefully. “We bought the debt. We really refinanced the debt and we inherited a management contract.”

Now a new owner is making a go of the business, with loans from Sea Hunter.

Confusion of local officials

The major players in this new big business operate nationally, but here, as ever in Massachusetts, all politics is local.

Municipal officials — whose approval is mandatory before companies can seek a state license — have a lot to sort through when it comes to marijuana applications. With the hope of new jobs and hundreds of thousands of dollars in tax revenue at stake, planning and zoning officials juggle the details of parking, security, and keeping drugs away from kids. They are rarely in a position to see through the opaque corporate relationships of those seeking their approval.

“ Who are we dealing with? ”

— A member of the Shrewsbury planning board at a hearing scheduled for a marijuana company called Prime Wellness Centers. The official would learn the company had been acquired by Acreage and would now be called The Botanist.

At a Shrewsbury planning board meeting in February, town officials expected to hear from a company called Prime Wellness Centers Inc., working its way through the system to open a marijuana store there.

But the businessman who settled in at the hearing table was not the person they knew from a prior hearing.

One planning member asked the obvious question: “Who are we dealing with?”

The man at the hearing table, Scott Rudy, turned out to be an Acreage executive.

“We’ve acquired the license — Acreage Holdings,” he said, adding, “We operate under the name The Botanist here in Massachusetts.”

Confusion over that name change ran even deeper in Worcester, which has been deluged by applications from 46 different marijuana-related businesses. Deputy City Solicitor Jennifer H. Beaton learned of the name change when she read about it in the newspaper.

That’s not how it’s supposed to work. Marijuana license holders are legally required to notify local officials before transferring a license. Beaton said the city is working with The Botanist’s lawyer to update their agreement, which had pledged annual tax payments of at least $120,000. Technically, the store should not be operating without an up-to-date host agreement, but Acreage skipped that step.

Companies failing to make such disclosures, with little to no enforcement by the state, are leaving towns and cities in the dark.

“It’s a big burden, one that we take seriously,’’ said Jacob Sanders, who handles intergovernmental affairs for the City of Worcester. “At the end of the day, our hope and expectation is that the Cannabis Control Commission is going to serve as the governing body that’s going to help municipalities.”