Michigan’s Adult-Use Rules Put Cannabis Pioneers Out in the Cold

Michigan’s first adult-use cannabis stores are expected to open near the end of 2019, but many of the state’s medical marijuana pioneers could find themselves shut out of the new retail industry.

The state's new adult-use rules require seriously deep pockets. That shuts a lot of locals out of the game.

The state has been in a scrambling-for-licenses stage since the passage of a statewide adult-use legalization initiative in Nov. 2018. Early indications are that those licenses are going predominantly to a few of the state’s biggest players—and not to the smaller caregivers who built the medical industry over the past ten years.

Michigan’s Marijuana Regulatory Agency (MRA), which oversees both the existing medical marijuana industry and the coming adult-use retail sector, released its rules and regulations for the recreational cannabis market earlier this month. While the new regs included a number of welcome deviations from the state’s draconian medical marijuana rules—such as eliminating the steep financial equity requirements for license applicants—the more restrictive medical regulations will remain in place for most applicants until late 2021. In other words: Forward steps are being made, but the state continues to tilt the field away from smaller entrepreneurs and experienced cannabis hands.

Take, for instance, the rules around cannabis farming.

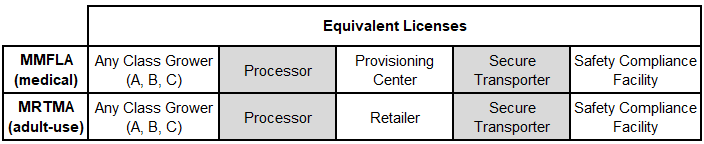

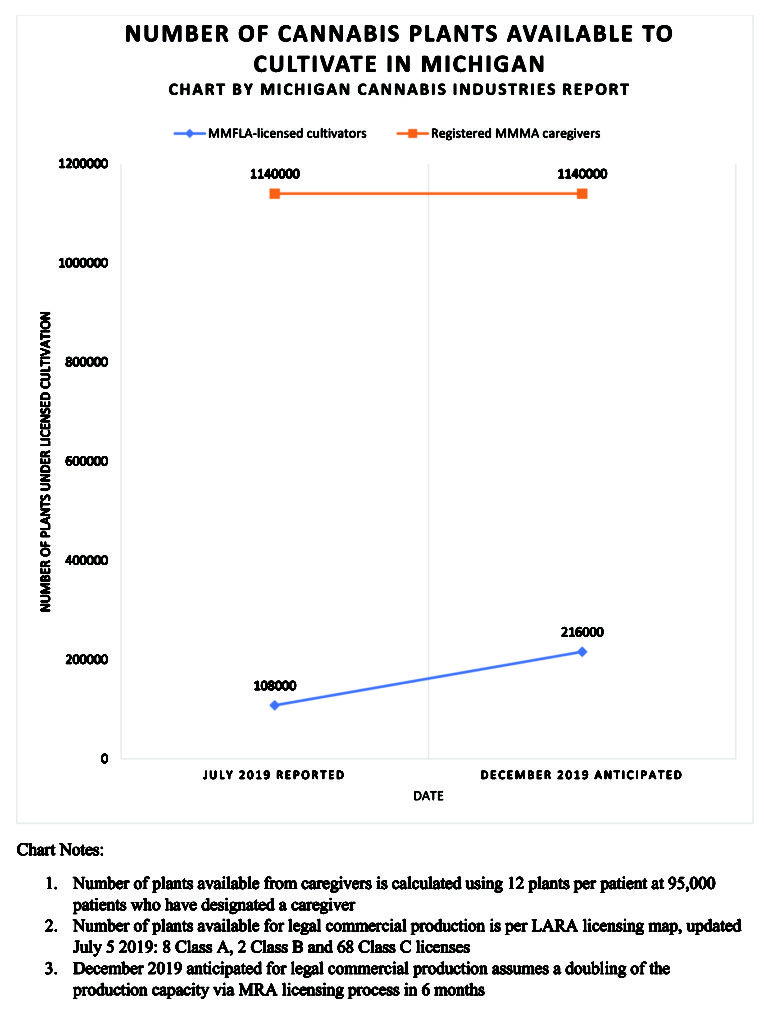

For medical cannabis farmers, the state is offering three classes of licenses: A, B, and C. Class A licenses are for small craft-scale growers with 500 plants or less. Class B are for moderate-scale commercial farmers with 1,000 plants or less. Class C is reserved for the biggest growers, with up to 1,500 plants.

Consolidation is happening fast. One company now holds eight grow licenses.

So far, the state has issued 67 grow licenses in the Class C category. Only 9 Class A licenses have been issued so far, and only one Class B license has been claimed.

This may be the most telling statistic: Those 67 Class C licenses, reserved for the biggest growers, are held by only 29 different growers. Eight companies hold multiple licenses. Green Peak, Michigan’s fastest-growing cannabis company, now holds 12 Class C growing licenses. Attitude Wellness, a Green Peak competitor, holds 9 Class C licenses.

“We’ve seen four and five applications for the same entity being approved simultaneously,” says Rick Thompson, a leading cannabis advocate and organizer of the Michigan Cannabis Business Development Conference.

Thompson is referring to the practices of the medical market’s now-defunct Medical Marijuana Facilities Licensing Act (MMFLA) Board. That board, appointed by the state’s previous governor, Rick Snyder, gained a reputation as the most anti-cannabis cannabis licensing board in the nation. It was comprised of two retired police officers, a pharmacist, a career Republican, and an automotive executive.

When Gov. Gretchen Whitmer succeeded Rick Snyder, she dissolved Snyder's notoriously anti-cannabis board.

The MMFLA process was notoriously unfriendly to anyone with limited financial means. Application fees ran upwards of $10,000, and a grow license could run nearly $50,000 on top of that. The state also required applicants to prove they had access to financing in the $150,000 to $300,000 range. Add to that the hefty fees charged by legal firms and consulting services, which are practically a necessity to prepare a proper application. “No small business could afford the expense up front,” says Thompson, “so bigger businesses have dominated the medical licensing process.”

MMFLA board members also gained a reputation for rejecting applications from longtime cannabis professionals for seemingly arbitrary and capricious reasons. When Gov. Gretchen Whitmer succeeded Snyder earlier this year, one of her first cannabis-related acts was to dissolve the MMFLA Board.

The legacy of that board remains, though. The big players who made it through the MMFLA licensing process have been scooping up market share by purchasing independent licenses, just as smaller dispensaries are being bought out by bigger retailers across the state.

On the west side of the state, White River Wellness and Emerald City Wellness were both acquired by Green Peak within the last year. Emerald City was one of the state’s many independent provisioning centers (a dispensary, in Michigan terms) operating on the old temporary caregiver laws, before the medical market’s regulatory system (MMFLA) was rolled out. “Those are the ones we’ve seen people go after,” says Connie Sparrow of Sparrow Consulting, a cannabis startup firm based in Michigan, “because [the owners] can’t get licensed and people want the real estate.”

In order to obtain a state license, the owner of a medical marijuana dispensary must undergo a forensic auditing process that’s been described by many experts as the most intensive facilities licensing investigation in the nation. It’s a process that all but requires a dispensary to hemorrhage funds to attorneys, accountants, and consultants.

“Small dispensaries are desperate for revenue,” Sparrow says, “so real estate investment trusts are coming in. The trusts want to invest, but [remain] an arm’s length away from the industry.”

“Everyone who’s coming in to invest in the industry wants to get out within a few years,” she adds, due to the current gold rush climate in Michigan.

With an existing medical market of nearly 300,000 patients and an estimated adult-use market of seven million, there’s certainly room here for big cannabusiness and then some—but size isn’t the only factor. Like the product itself, the market share growth of big companies has carried an entourage effect. Big companies come into the state, but they don’t necessarily hire within the state.

Michigan-based agencies, consultants, and freelancers who worked to build independent brands, are feeling snubbed.

A number of brands represented by large out-of-state trusts have hired their ancillary service providers—attorneys, PR firms, branding agencies and other consultants—out of New York or Chicago, instead of from local talent pools. Michigan-based agencies, consultants, and freelancers who worked to build independent brands are feeling snubbed.

The state’s strenuous employee background requirements play into this dynamic. Many of Michigan’s most experienced cannabis employees, consultants, and experts have worked in the industry here for years. And the state’s law enforcement agencies have been raiding and arresting dispensary and cannabis farm employees for years. So finding local talent with both growing experience, or dispensary experience, and a clean law enforcement record, can be a challenge.

It can be especially difficult to staff up with an eye toward both cannabis experience and diversity, as people of color have been subjected to decades years of racially biased policing on all levels, and especially when it comes to cannabis.

Past Cannabis Offenses Are a Barrier

“I cannot find a single African American person who has growing experience who doesn’t have a felony—not one,” says Sparrow, who often takes pro bono clients. Obviously, not all people of color who grow cannabis in Michigan have criminal records. But Sparrow’s comment illustrates the frustration that many in the industry are feeling right now.

“The biggest problem is reparations,” Sparrow adds. “We have to figure out what we’re going to do with the black and brown people who have been locked up for years. If the conglomerate corporations have really good missions where they’re trying to create equity and diversity in their workforce, I think they should be forced to hire the felon.”

Prior felonies for marijuana-related crimes have kept individuals from participating in Michigan’s legal market as caregivers and license holders. Now they’re threatening to keep those drug war victims out of the legal adult-use industry, too.

“So which is the big monster,” asks Sparrow: “big business, or felony convictions? You’re still losing half the workforce.”

There may be at least a little help on the way. On July 18, Michigan’s MRA released the details of a new social equity program, which would reduce recreational licensing fees for residents of 19 communities that have been identified as being “disproportionately affected” by the war on drugs. The newly announced program also includes extra provisions for those with past marijuana-related crimes and/or who had been caregivers. While medical licensing requirements will still apply to adult-use businesses sized class B and up, the new program does have the potential to open up opportunities for small canna business growth in a few high-need areas.

A Two-Year Head Start

The MRA’s new rules for adult-use marijuana facilities do not include the high financial equity requirements for applicants, and many see that as a big step toward opening the licensing process to smaller-scale local operators. But there’s a catch. The new law says that applicants for adult-use licenses must also meet the existing medical cannabis requirements for a full two years after the new adult-use regulatory system is up and running. So really, the big financial hurdle is still in place until, possibly, November 2021.

The biggest financial hurdle will remain in place until the end of 2021.

“That was included to prevent the recreational licensees from having an unfair advantage over the applicants who’ve just gone through the medical licensing,” explains Matt Abel of the law firm Cannabis Counsel. There is an exception for micro-businesses and applicants for Class A grow licenses, but many are concerned that this “zombie” financial equity requirement will act as one more barrier keeping smaller-scale local companies out of the industry.

“The real problem is that the legislature created such a burdensome [medical] regulatory program” under former Gov. Snyder’s MMFLA, says Rick Thompson. “It took a long time to get rolling, then the board created a whole new set of problems with licensing. So I blame the legislature. We’ve had business licensing for a year, and we still can’t supply 300,000 [medical cannabis] patients. That’s not a good result.”

Even if the MRA’s new financial rules won’t apply to medium and large scale growers for at least two years, it’s possible that they could prompt a change in the regulation of the current medical market. “There is no mention in the medical statute for a capitalization requirement,” says Denise Pollicella of Cannabis Attorneys of Michigan, referring to the original Michigan Medical Marihuana Act of 2008. “I think the fact that the MRA chose not to continue those capitalization requirements in the rec rules completely undermines the [rationale for the] capital requirement for medical facilities.”