Roberto Gonzalez, the general manager of Western Oregon Dispensary in Sherwood, Ore., waits for customers. The dispensary is one of two medical-only marijuana dispensaries left in Oregon. | Gillian Flaccus/AP Photo

State efforts to grow pot industries clash with federal law

Insurers won’t cover drug the feds still ban.

This story was published as part of a POLITICO Journalism Institute special section. PJI is a journalism training program in partnership with American University and the Maynard Institute, that allows student participants to report and produce news stories.

State legislatures across the country are taking steps to protect medical marijuana users, but many patients face hurdles when accessing the drug because insurance companies won’t cover a substance that remains illegal under federal law.

Illinois is poised to become the latest state to legalize adult recreational use of marijuana, and the bill approved by the state Legislature on May 31 would allow medical users to grow marijuana at home and require cannabis businesses to keep reserves for patients in case of shortages.

New Jersey’s Department of Health announced Monday that it will

significantly boost the number of licenses it distributes in hopes of expanding the state’s medical marijuana program.

But accessing medical marijuana remains difficult for some patients, even in states that hope to permit its use, cannabis advocates say. Because cannabis remains classified as a Schedule 1 drug under the Controlled Substances Act, the Food and Drug Administration has not approved it to reduce pain, treat anxiety or provide other much-touted health benefits.

Typically, insurance companies cover the costs of only FDA-approved drugs, so patients cannot use their health insurance policies for their prescription or application fee, said Shanita Penny, president of the Minority Cannabis Business Association, a lobbying group. Those patients have to pay out-of-pocket costs that Penny said can add up to more than $900 in some states after patients pay the application fee, buy required paraphernalia and obtain the drug.

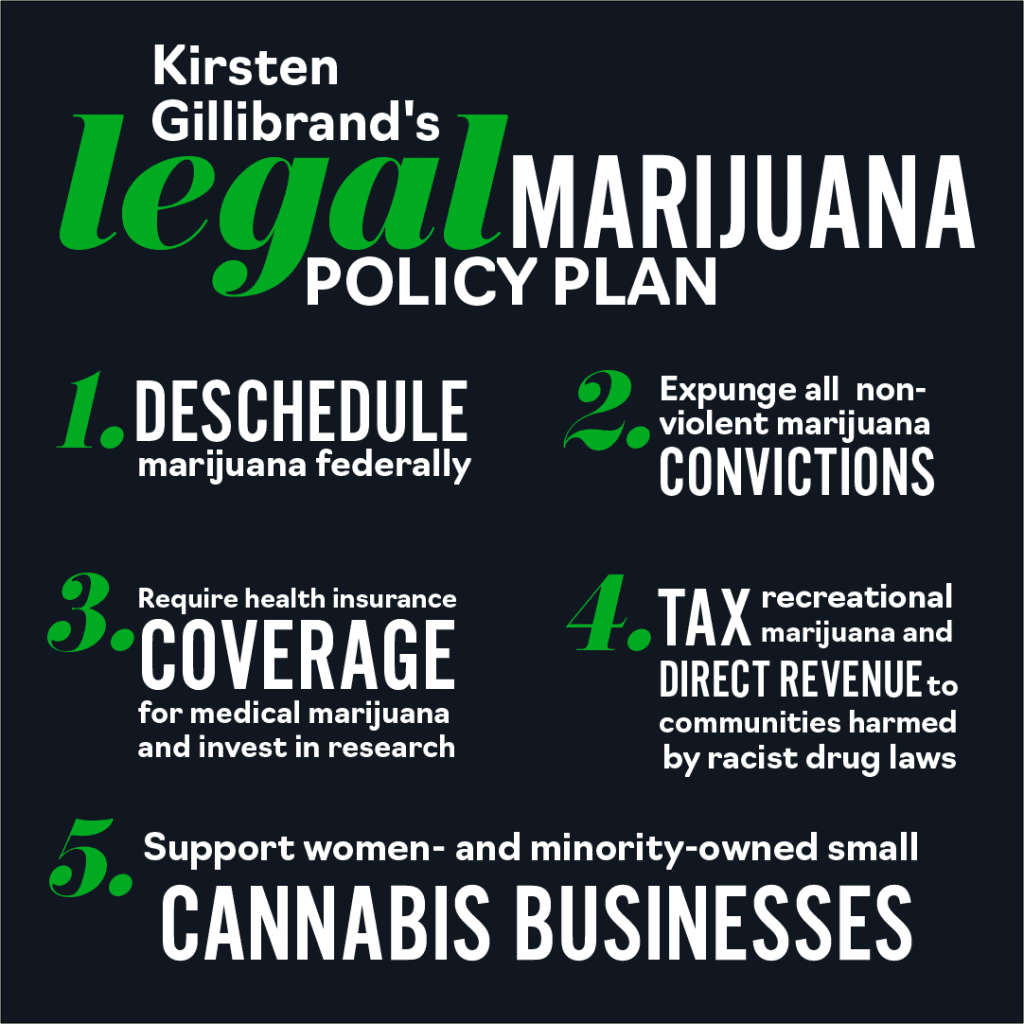

Virtually every Democrat seeking the party’s 2020 presidential nomination has called for legalizing adult recreational use. Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) on Wednesday

unveiled a plan that would include requiring health insurers, including Medicaid and Medicare, to cover medical marijuana.

“We’ve made great progress in recent years on legalizing marijuana at the state and municipal level, and we’ve seen the positive benefits in states like Colorado, Washington, and more,” Gillibrand said in a statement. “But a state-by-state patchwork is not enough to tackle the deeply rooted racial, social, and economic injustices within our marijuana laws, or to fully unleash the economic equity and opportunity of marijuana legalization.”

Under the current system, the high cost of regulated medical marijuana puts it out of reach for many patients who would otherwise be eligible to use it. They include many people of color, who have also been disproportionately affected by marijuana law enforcement, according to

several studies. The

Drug Policy Alliance found in 2018 that while arrest rates for marijuana possession have decreased as more states legalize the drug, Latinx and black people are still more likely to be arrested despite similar usage rates among white people.

Penny said some dispensaries work to have discounts for veterans or patients, like gifting $50 worth of medicine if the application fee is $50, but the recurring cost of the drug is too expensive for some.

Penny said that burden is leading some patients who could obtain marijuana from state-approved businesses to buy it more cheaply from dealers who operate illegally.

“They’re not seeking it from a dispensary because the price point is too high,” Penny said. “You do see, especially people from minority communities, folks that are low income, continuing to purchase this medicine from the unregulated market. Because it is at least accessible to them still.”

Including Illinois, 10 states and the District of Columbia have legalized recreational marijuana use by adults, and 33 states have approved its use for medical purposes, which Penny said can include preventing nausea, such as among chemotherapy patients, and treating epilepsy. But federal rules have hindered the industry’s growth by

making banks wary of working with pot businesses and

blocking research into the drug’s effects.

Some lawmakers are trying to fix that gap between state and federal law, with little success so far. One proposed solution is a bill introduced by lawmakers from states with legal marijuana markets, including Colorado and Massachusetts. The STATES Act would exempt individuals and corporations who comply with state marijuana laws from federal law enforcement.

Critics, however, say that approach would just add complexity since it does not address the Schedule 1 classification. And opponents of legalization, including many congressional Republicans, say marijuana is a dangerous substance that should not be accessible. Colton Grace of the anti-pot legalization lobbying group Smart Approaches to Marijuana said states that are allowing marijuana use do so for commercial reasons.

“The industry is not interested in public health and safety, they’re interested in profit,” Grace said. “Because of that, they’re doing anything they can to roll back regulations and increase that profit.”

But states that have legalized marijuana have more regulation, making the product safer, according to Penny.

Mischa Sogut, legislative director of New York’s State Assembly Health Committee, said the state’s health department is working to create a more accessible medical marijuana program. According to the

department's website, it waives the $50 application fee required by the state’s 2014 Compassionate Care Act for all patients and their caregivers.

Still, Sogut said prices at dispensaries in New York can vary and some dosages are priced high in an effort to make a profit. The lack of insurance coverage for marijuana hurts businesses’ ability to expand, Sogut said.

It’s hard “to lower prices too much as long as they’re not profitable, but if they don’t lower prices, since it’s not covered by insurance, it limits their ability for patients to pay, and then they can’t bring in more patients,” Sogut said. “They’re in a bit of a circle with this.”

Furthermore, federal Medicaid plans do not cover the cost of the drug, even if a physician recommended it. State Medicaid programs in legal states may offer coverage if no federal funding match is requested, Sogut said, adding that New York could create a pilot program for marijuana similar to its coverage for abortions and services for undocumented immigrants.

However, he said a federal solution is needed for commercial insurance companies, which comply with federal law even though they’re permitted to cover cannabis under New York law.

“There are things you can do, but I don’t think you’re going to get to widespread, universal commercial insurance coverage until there’s a federal change,” Sogut said. “If there’s a federal change, that’s when you’ll start to see [marijuana] on drug formularies like a normal health care prescription drug.”

Justin Strekal, political director for the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, said states could also drive down costs for patients by relaxing limitations on dispensaries and growers and approving more permits.

“When you have a very limited number of businesses competing for consumers, due to arbitrarily decided licensing accounts, it runs contrary to American principle of a free marketplace,” Strekal said. “There’s no logical justification other than pure greed to restrict the number of licenses being issued.”

Illinois state Sen. Heather Steans, a co-author of the recently passed bill, said that her state’s medical program is well-regulated. She said the legislation would lead to new tax revenue that will be used to reinvest in communities that have disproportionately been targeted by drug enforcement.

Still, she said federal law needs to change to make medical marijuana more accessible.

“As states continue to make changes on cannabis laws, I think the federal government needs to act. Federal lawmakers really do need to act,” Steans said.

My favorite line of the entire article:

My favorite line of the entire article: