The Band's guitarist and primary songwriter collaborated with Bob Dylan and penned "The Weight," "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," and "Up On Cripple Creek," among other classics

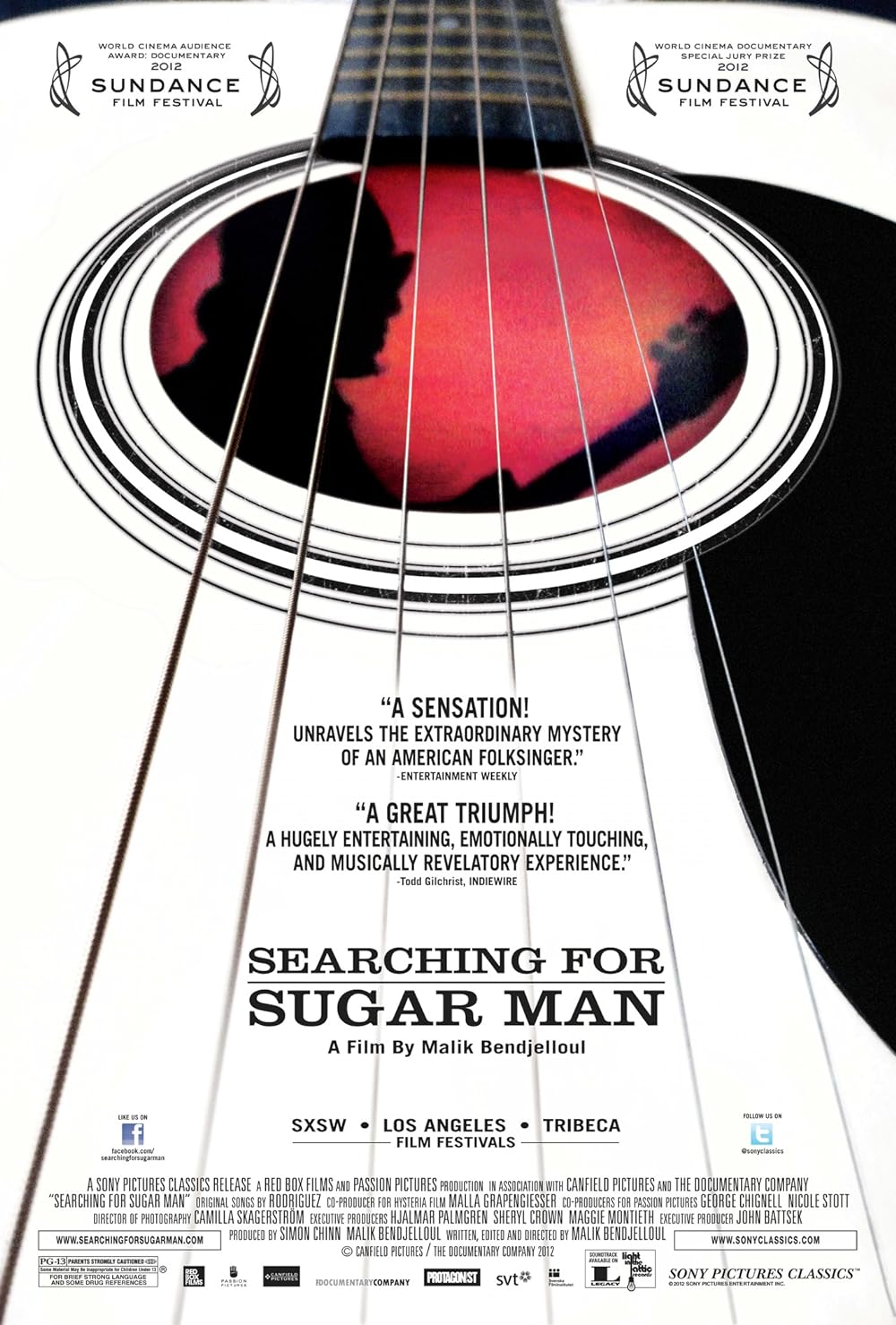

View attachment 48439

ROBBIE ROBERTSON, THE Band’s guitarist and primary songwriter who penned “The Weight,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “Up On Cripple Creek” and many other beloved classics, died Wednesday at age 80.

Robertson’s management company confirmed the musician’s death. “Robbie was surrounded by his family at the time of his death, including his wife, Janet, his ex-wife, Dominique, her partner Nicholas, and his children Alexandra, Sebastian, Delphine, and Delphine’s partner Kenny,” his longtime manager Jared Levine said in a statement. “In lieu of flowers, the family has asked that

donations be made to the Six Nations of the Grand River to support the building of their new cultural center.”

The Band only lasted eight years after the release of their 1968 debut LP

Music From Big Pink, but during that time they forever changed the pop culture landscape by releasing brilliant Americana music at the peak of the psychedelic movement. Their first album sent shockwaves through the industry,

inspiring Eric Clapton to break up Cream, the Beatles to attempt their own stripped-back project with

Let It Be and a pair of young British songwriters named Elton John and Bernie Taupin to begin writing and recording their own material.

Robertson took on the role as the group’s leader, writing the majority of their songs and pushing them forward when substance abuse issues and infighting threatened their existence. It was also his decision to pull the plug on the group in 1976 when he couldn’t take it anymore, setting the stage for their

legendary farewell concert The Last Waltz.

“The road has taken a lot of the great ones,” he said at the time. “Hank Williams, Buddy Holly, Otis Redding, Janis, Jimi Hendrix, Elvis. It’s a goddamn impossible way of life.”

Before the Band began making their own music, Robertson was one of Bob Dylan’s key collaborators, playing guitar on

Blonde on Blonde and convincing the songwriter to hire the other members of his group as his backing band. They toured the world in 1965 and 1966, facing a torrent of boos by enraged folk purists. “His friends, his advisors and everyone told him to blow us off and start from scratch,” Robertson said in 1987. “And it took a tremendous amount of courage for him not to do that.”

Born in Toronto, Canada on July 5th, 1943 to a Native American mother and Jewish father, Robertson was fascinated by music from a young age. “I’ve been playing guitar for so long I can’t remember when I started,” he told

Rolling Stone in 1968. “I guess I got into rock and roll like everybody else.”

He left high school long before graduation to tour Canada with a series of rock bands, joining rockbabilly icon Ronnie Hawkins’ backing band when he was 16. “We played everywhere,” he said, “from Molasses, Texas to Timmins, Canada, which is a mining town about 100 miles from the tree line.”

It was in Hawkins’ band where he first played with drummer Levon Helm, keyboardist Richard Manuel, organist Garth Hudson and bassist Rick Danko. They formed a tight musical bond, which continued when they hit the road with Dylan in 1965. “I had never seen anything like it,” Robertson said in 2004. “How much Dylan could deliver with a guitar and a harmonica, and how people would just take the ride.”

In early 1966, during a break from the tour, Dylan brought Robertson down to Nashville to play guitar on his landmark double-album

Blonde on Blonde. “We’d go into the studio, and he’d be finishing up the lyrics to the songs we were going to do,” Robertson said. “I could hear his typewriter – click, click, click, ring, really fast. There was so much to be said.”

The tour came to a sudden end in the summer of 1966 when Dylan crashed his motorcycle in Woodstock, New York. But a few months later, Dylan summoned Robertson and company to Woodstock to begin work on a series of home recordings later known as

The Basement Tapes. “We thought nobody was ever going to hear this thing,” Robertson said decades later. “In their own way, they were like field recordings.”

Dylan resumed his own career in 1968. Around that time, the group re-dubbed themselves the Band. “There aren’t many bands around Woodstock and our friends and neighbors just call us the Band and that’s the way we think of ourselves,” Robertson said in 1968. “We just don’t think a name means anything. It’s gotten out of hand, the name thing. We don’t want to get into a fixed bag like that.”

When they began writing songs for their first LP, Robertson stepped forward as the leader in the process. In a 1969 interview with

Rolling Stone, the guitarist attempted to explain how he wrote “The Weight.” “I thought of a couple of words that led to a couple more,” he said. “The next thing I know I wrote the song. We just figured it was a simple song, and when it came up we gave it a try and recorded it three of four times. We didn’t even know if we were going to use it.”

Needless to say, the song wound up on

Music From Big Pink and generated radio play all over the world, generating cover versions by the Staple Singers, Joe Cocker, the Grateful Dead, Aretha Franklin and countless others.

Over the next eight years, The Band scored more Robertson-penned hits (“Up On Cripple Creek,” “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” “Stage Fright,” “The Shape I’m In”), played Woodstock, toured the world many times over and reunited with Dylan for a hugely successful stadium tour.

By 1976, the Band bassist Rick Danko and keyboardist Richard Manuel developed severe substance abuse issues, and Robertson – who had effectively been on the road since 1959 – was burned out. “The road turns you into a meaningless piece of dribble that will complain about shit that doesn’t mean anything to anybody,” he said in 1987. “It got to the point where I couldn’t see the upside.”

Robertson decided that the Band should go out with a bang, so he organized a massive farewell gig at San Francisco’s Winterland Ballroom and invited everyone from Dylan to Neil Young to Muddy Waters and Hawkins to guest. Martin Scorsese filmed the event, which was released in 1978 under the title

The Last Waltz. It’s widely seen as one of

the greatest concert films of all time, even though Helm felt it focused way too much attention on Robertson at the expense of other members of the group.

It was the beginning of a long feud with Helm over credit and songwriting royalties that was never fully resolved, though Robertson did visit his old friend in the hospital during the final days of his life in 2012.

The Last Waltz was also the beginning of a tight bond between Robertson and filmmaker Martin Scorsese, who hired the songwriter as the musical supervisor for his movies

The King of Comedy, Casino, Gangs of New York, Shutter Island and

The Wolf of Wall Street. Robertson had a role in the 1980 film

Carny, and the documentaries

Dakota Exile (1996), and

Wolves (1999). In 1967, Robertson married Canadian journalist Dominique Bourgeois, with whom he had three children. They later divorced. In 2014, Robertson’s son Sebastian published a children’s book,

Rock and Roll Highway: The Robbie Robertson Story, about his father’s life and legacy.

Keeping the promise of

The Last Waltz, Robertson never returned to touring, though he did release five solo albums beginning with 1987’s critically acclaimed

Robbie Robertson. In 2011, he collaborated with Eric Clapton, Steve Winwood, Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello and Trent Reznor of Nine Inch Nails on the blues-steeped

How to Become Clairvoyant.

His most recent solo release was

2019’s Sinematic, which featured guest appearances by Van Morrison, Derek Trucks, and Citizen Cope. He also oversaw the music for Scorsese’s

Silence,

The Irishman, and the upcoming

Killers of the Flower Moon, capping off a five-decade relationship with the director that stretched back to

The Last Waltz.

In 2016, he published the memoir

Testimony, following it up in 2019 with the documentary

Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band. At the time of his death, he was working on a second volume of his memoir series. “There is something blatantly honest about this period I’m in now, what I’m drawn to,” he

told Rolling Stone in 2019. “I guess I’m at an age now – a place in my journey – where I don’t care what you think. I’ll tell you anyway!”